[ad_1]

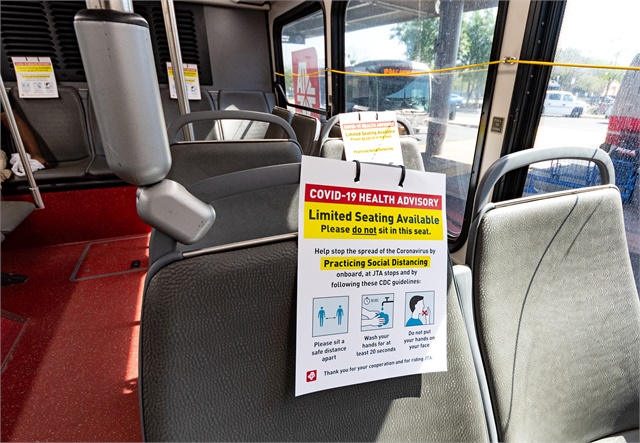

When a threat is ever present, the brain will naturally fight to remain focused only on that until it perceives that one’s body, loved ones, and the general environment are once again safe. JTA

As transit worker deaths increase from COVID 19 in the Northeast, and the virus spreads throughout all our communities, public transit employees are experiencing overwhelming stress. The frontline workers are understandably gripped with anxiety that they will fall ill or pass the virus to loved ones at home. We know that burnout is the result of a combination of long work hours without a break, a lack of control over one’s environment, a belief that the reward isn’t worth the risk, and a sense that things are unfair. I can’t think of anything that sets essential workers up for intense burnout and trauma more than a pandemic. And yet, it’s becoming increasingly clear the only way out of this is through it. Essential workers will not get a break. The long hours will continue. The risks will be great. The sense of unfairness mounting.

Fear, particularly when it’s sustained over a period of time, reorganizes the brain, cutting off the normal pathways to problem-solving. When the threat response is activated, the autonomic brain will have one of four reactions: fight, flee, freeze, or fold. Certainly, the riding public is behaving erratically due to this toxic stress, making the frontline’s work that much more difficult. Despite reduced service, transit control centers may be registering a higher volume of calls from the frontline due to the chaos. It’s also likely the stress on essential workers causes them to reach out more rather than use their usual coping mechanisms.

Operators, field supervisors, conductors, and maintenance personnel may find it harder to complete tasks that were once manageable. They also may be struggling to come to work, snapping at customers, or simply shutting down and numbing out. These are not signs of weakness, they are human survival techniques deployed during an overwhelming crisis.

Management is also at risk. They directly support the frontline and may feel helpless to respond to their team’s greatest needs, which are adequate PPE, enough police to manage the social breakdown in our communities, and in some cases, extra personnel to share the work. Recognizing the limitations of the support that management can offer is a bitter pill to swallow for everyone.

Support through acknowledgment and thanks is an important gesture but it can’t be the only gesture. Additionally, we know that self-care is crucial for all involved but the practice of self-care often feels like an added task on the enormous checklist for both the frontline and their management. And effective self-care practices may vary from person to person. For instance, the idea of meditation for some team members may feel like total nonsense. For others, it can be a lifesaver for bringing one’s autonomic nervous system out of threat mode, even if it’s for a short time.

Most transit organizations have already institutionalized wellness programs for employees to access. In addition to counseling through EAP, they’ve installed exercise equipment, created quiet rooms for split shifts, and offered nutrition programs. If employees aren’t already in the practice of using these tools, it’s going to be tough getting them to start now. Even for those who regularly use them, it’s harder to access, not just because leisure time is rare, but because they don’t feel the threat ends when they leave the public space. Exposure to the illness may take days to weeks to show up and the essential service worker may be bringing catastrophic illness to loved ones, creating a sense of carrying a ticking time bomb. When a threat is ever present, the brain will naturally fight to remain focused only on that until it perceives that one’s body, loved ones, and the general environment are once again safe.

To complicate matters, consider that both calm and fear are contagious among humans. We read each other’s faces, voice tones, and body language to determine whether an environment or individual is dangerous or safe. We know that when we’re under stress, and we see a friendly face communicating concern, it helps put us at ease. This coregulation of emotions is how healthy communities thrive. Social distancing, wearing face masks, and having to shout to one another to give and receive information is necessary to stop the spread but exacerbates our collective panic.

|

Managing to move forward

The transit industry is adept at managing complex systems, minimizing risk despite shrinking budgets, and ensuring safety as its number one priority. It responds effectively to critical incidents such as hurricanes, gas leaks, and train derailments. But the scale of this crisis is unprecedented and will play out as a marathon that we’ve not prepared for rather than a sprint. Transit is burdened with playing a supportive role in the crisis response to this pandemic. And because of that, it is nearly last in line for receiving PPE in this national shortage. That’s what we’re up against: a vicious virus, a loss of safe community, and no clear long-term strategy to navigate our way through it.

Transit staff will have to rely on each other’s support and the support of other agencies to overcome this using virtual communication tools that will initially feel awkward such as Zoom and Webex. It’s not ideal but communication with one another has never been more important.

When communicating support, recognize that your goal is to build resources that essential service personnel can access to create safety. Specifically, identify resources one can access to create a sense of safety both in the work environment and in the body where stress is wreaking havoc.

Red Kite Project recommends several actions to assist:

1. Establish micro teams of groups of three or four who can rely on each other to share concerns and provide mutual support.

2. Act as liaison between your frontline and other community support systems. Specifically, provide information regarding childcare. Some school districts across the country are offering childcare services for essential workers.

3. If you have a mentoring program, strengthen it and ask them to reach out to mentees more often than normal.

4. Ensure your EAP is offering telehealth services for counseling sessions.

5. Maintain transparency with all teams. Daily memos and verbal briefings with middle management to ensure everyone has the same information. Keep union leadership up-to-date. Be open to suggestions.

6. Ask individuals what they need before forcing something on them that they don’t want or can’t tolerate. If they ask for something you’re unable to give them, explain what the obstacles are, what you’re doing to remedy it and what the expected timeframe for arrival is. Keep them in the loop.

7. This next recommendation will sound counterintuitive to transit culture but it’s crucial to bring moments of gentleness in your conversations with others and in your own self-talk. For essential workers and their families, the next weeks and months may be the harshest experiences of their lives. Certainly, that’s what many in the northeast are experiencing right now.

What is gentleness? It’s the removal of self-blame and judgment. It’s the self-acceptance that this is how you’re feeling and what is happening to your body and your community. It’s the acknowledgment of grieving for a time when we were someone different as individuals and as a collective. It’s leaving open a window of hope that as a community we will come through this together to heal.

Charlotte DiBartolomeo, M.A.C.T., is Founder & CEO at Red Kite Project