[ad_1]

Federation Brewing co-founder Aram Cretan

Camille Snell

At Cellarmaker Brewing in San Francisco, Monday is now beer canning day. A few blocks away, ThirstyBear is putting beer in cans for the first time in its 24-year history. And on the other side of the Bay Bridge in Oakland, Federation Brewing is dependent on canned beer as its keg business has dried up.

Across the Bay Area, where the craft brew craze has exploded over the past decade, small breweries have gone almost two months without serving customers in pubs and restaurants. Through a combination of government-backed loans, hefty cost cuts and curbside pickup, they’re hoping they can do just enough to outlast the coronavirus pandemic.

When it comes to generating revenue from their main product, brewers have discovered that it’s all a matter of what they can tastily fit into aluminum. The margins are slimmer, materials costs are higher and shipping across the state can be burdensome, but cans have suddenly emerged as an unexpected lifeline for breweries that have few other options.

“It’s can or die right now,” said Connor Casey, co-owner of Cellarmaker, which owns House of Pizza in San Francisco in addition to its brewery and tap room. “There’s not even a choice.”

Cellarmaker’s business is down by about half from before the crisis, a similar picture to what’s happening nationwide. A survey conducted in late March by the Brewers Association, which consists of over 5,400 members, found that sales at the average small brewery are off by 60%, and more than a quarter of them had stopped production. Based on data the group published last year, California is the top state for craft breweries, with 907, more than triple the figure from 2012 and over twice as many as second-ranked Colorado.

Casey, who helped open Cellarmaker in 2013, said he would normally can beers once every three to four weeks. Now, with $7.50 draft pints off the table, Cellarmaker is canning almost all of its beer weekly and shipping 24-can cases across the state —a different combination package every week based on what it brewed — or selling four-packs to consumers who come to the pizzeria for take-out. The average price for a canned pint is about $3 less than on draft.

Cellarmaker beers

Douglas Rodriguez

Demand isn’t the problem — alcohol sales are up across the country. For craft beer, sales rose 5.8% from a year earlier in the week ended April 18, according to Nielsen. But for breweries like Cellarmaker that rely on fresh pints from the keg and don’t have established relationships with big supermarkets, the economics can’t work for long.

“Nobody is thriving right now,” said Casey, who’s had to furlough about 60% of his staff. “Keg beer is dead, and for us that’s really tough.”

Canning on wheels

Craft breweries are only able to can in mass quantities because of operations like The Can Van, a small nine-year-old rolling shop based in Sacramento.

The 22-person company deploys seven vans to breweries in the region, and has thrived in recent years as craft breweries turned to cans over bottles because they’re lighter, cheaper to ship and, according to many connoisseurs, maintain a fresher quality. Now, one of its big tasks is helping beermakers empty their tanks into cans so their production doesn’t go to waste. That’s particularly important for breweries that specialize in India Pale Ales (IPAs) and aromatic hazy beers, which are heavy on hops and have a shorter shelf life than lagers, porters and stouts.

“When the stay-in-place order came down, there was lot of beer already in the tanks that people didn’t have a destination for,” says co-founder Jenn Coyle. “This just allows you to sell it.”

To keep her staff safe and maintain social distancing, Coyle has limited jobs to teams of two people. Setting up the equipment, hooking up to the water and electricity and canning the beer takes anywhere from a few hours to a full work day, depending on how many cases are being filled. Each van is typically doing one project a day, though demand is so high that they’re now working Saturdays.

Clients range from younger breweries like Cellarmaker and Temescal Brewing in Oakland to established institutions like Sonoma’s Russian River Brewing, home of the famous Pliny the Elder Double IPA. Coyle said the Can Van had never previously worked with Russian River pre-coronavirus, but is now there multiple weeks a month, canning a Happy Hops IPA, a hazy named Tempo Change and a hoppy ale called Dribble Belt, which Russian River’s website says is “pub draft only.” Breweries hire their own artists for the labels, and The Can Van brings all the canning supplies.

Almanac’s SIP beer

Ari Levy | CNBC

Some brewers are getting extra creative to keep their product moving.

Temescal, founded in 2016, is getting thematic with its beers, rolling out an Italian-style lager called Canned Vacation, in collaboration with Almanac Brewing, based in neighboring Alameda. “Canned Vacation is our little tribute to all those vacations that got the can this past month,” Temescal says on its Facebook page.

Almanac, which opened its 30,000-square foot Alameda facility in 2018, has another new canned beer called SIP: Shower In Place, a hazy double IPA. “We’re all spending a lot more time at home these days, but you can still take an exotic tropical journey from the comfort of your house!” the website says.

‘Big nut to crack’

The Bay Area’s craft brewers were already facing challenges before Covid-19 struck.

Competition is stark, overhead costs are high and the price of living is astronomical, largely because of the wealth from the tech industry. According to PropertyShark, 91 of the top 100 most expensive ZIP codes in the U.S. last year were in California, including 13 in San Francisco.

ThirstyBear, located next to San Francisco’s Moscone Center, has been closed since Gov. Gavin Newsom’s shelter-in-place order in March. Even though restaurants can stay open for takeout, ThirstyBear owner Ron Silberstein opted to close because without the convention business and visitors to the downtown museums, there wouldn’t be enough foot traffic.

But as the shutdown period lengthened, Silberstein started preparing a to-go menu. He also called up The Can Van, and in late April Coyle’s team canned 400 cases of ThirstyBear’s IPA, lager, red ale and pilsner that were in barrels and needed to hit the market.

“We have a big nut to crack,” said Silberstein, whose brewery sits in an 18,000 square-foot space with a restaurant that’s accustomed to selling $30 paella dishes and $7 to $9 pints of organic beer, while also hosting high-priced banquets. “Our business model is the social business model. It’s people coming together in large groups.”

Silberstein also owns a malting business in Alameda called Admiral Maltings, which he said has seen a 70% to 80% dropoff in sales to brewing customers. His taproom, the Rake, is still selling canned beer from breweries that use his malt.

The Rake in Alameda

Ari Levy | CNBC

In Oakland’s Jack London District, on the far west side of town, more than a half-dozen breweries dot an old industrial neighborhood. For several hours a day, consumers can drive up to Federation Brewing, Oakland United Beerworks or Original Pattern and pick up four-packs of cans at curbside.

They can also get order to-go beer from kegs poured directly into growlers (64-ounce jugs) or crowlers, which are 32 ounce cans that are individually sealed by a machine immediately after the pour. That’s about the only beer coming out of kegs these days.

Oakland United Beerworks

Ari Levy | CNBC

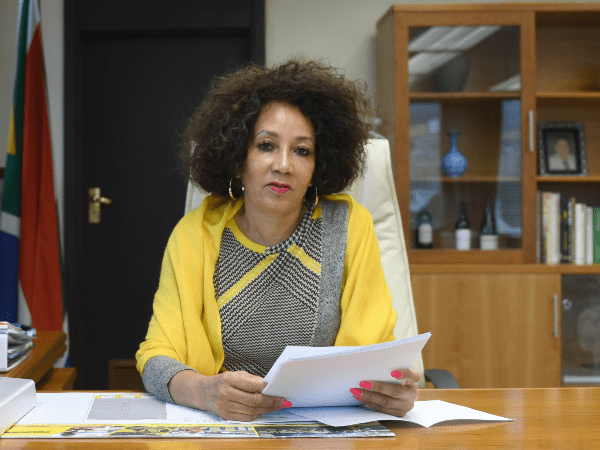

Federation co-owner Aram Cretan is exploring every avenue available. After the shutdown order in March, his brewery quickly set up a website for to-go and delivery orders, even getting into the subscription business. Starting at $60 every two weeks, customers can join the SIP (shelter-in-place) club and get four four-packs, so you can “sip while you SIP,” the site says.

Cretan said the effort has been “remarkably successful,” and that about 25% deliveries are for people buying beer for friends and family members. He’s made certain changes, like canning a German-style Dunkelweizen beer that would normally just be sold on draft, and is selling a lot of milk stout in crowlers. He’s considering creative ways to age certain types of beers that hold up over time and is looking to brew beers that can sit for longer in tanks.

It’s still not nearly enough to compensate for the loss of Federation’s core business, which is selling kegs to local bars and fresh pints in its taproom to the hundreds of customers that would stream through over the course of a weekend. Those revenue options are shut off for the foreseeable future, and Cretan estimates 100-150 kegs are in jeopardy of expiring.

“I’m sitting on a ton of keg inventory, a lot of which is going to have to go down the drain,” Cretan said. “Any beer that any brewery had in kegs when this thing started is pretty much a write-off.”

Federation was lucky enough to get money from the government’s paycheck protection program, so it can at least temporarily pay most of its 10 part-time and full-time employees to “not do a whole hell of a lot right now,” Cretan said. He knows that money will run out long before business returns to normal, if it ever does.

Coyle has the same long-term concern. Even though The Can Van’s business is thriving at the moment, she needs breweries to find their way through the crisis, so her customers are still around when it’s over. She’s doing what she can to help. Rather than forcing customers to do can the typical minimum of 150 cases, The Can Van is now doing some smaller gigs as long as it’s able to cover its costs.

“We really want all these breweries to be here in six months,” Coyle said, as she was en route to a canning at Oak Park Brewing in Sacramento. Her company had been working with the brewery on a Kolsch beer that was intended for Sacramento beer week, starting in late April.

The festival was canceled, but the 53 cases of beer were ready for canning, and The Can Van obliged. They named the beer Curbside Kolsch. A four-pack can be picked up for $14.

WATCH: Here’s how coronavirus is impacting the craft beer industry