[ad_1]

The coronavirus has put America’s housing market on hold. As residents shelter in place, real estate listings have slowed to a trickle. State and federal policymakers, facing an unprecedented spike in unemployment and a pandemic simultaneously, have banned evictions to ease economic hardship during the crisis.

But eventually all of this will have to end. When the eviction bans expire, millions of Americans will find themselves on the hook for months of back rent. Thirty million Americans — overwhelmingly the poor and renters — are newly jobless as unemployment hits previously unthinkable levels.

“Eviction moratoriums are a great first step, but there’s a lot of evidence that landlords are still filing for eviction,” said Megan Hatch, a professor at Cleveland State University who studies urban policy. “When these restrictions are lifted, a huge number of people could be evicted right away.”

May 1 is the second rental due date since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Millions of renters will have to choose between paying their rent and buying essentials. Some have already reached the bottom of their savings.

Even before the pandemic, a significant percentage of Americans were struggling to pay rent. In a 2018 Pew Charitable Trusts survey, nearly 1 in 6 households reported spending more than half of their income on rent. Of the roughly 19 million American families who are eligible for rental assistance, only 4 million receive it.

In April, almost one-third of households said they couldn’t pay the rent. May is not looking any better.

“We know millions of households were one financial accident away from eviction,” said Sarah Saadian, the vice president of public policy for the National Low Income Housing Coalition. “This pandemic may be the breaking point.”

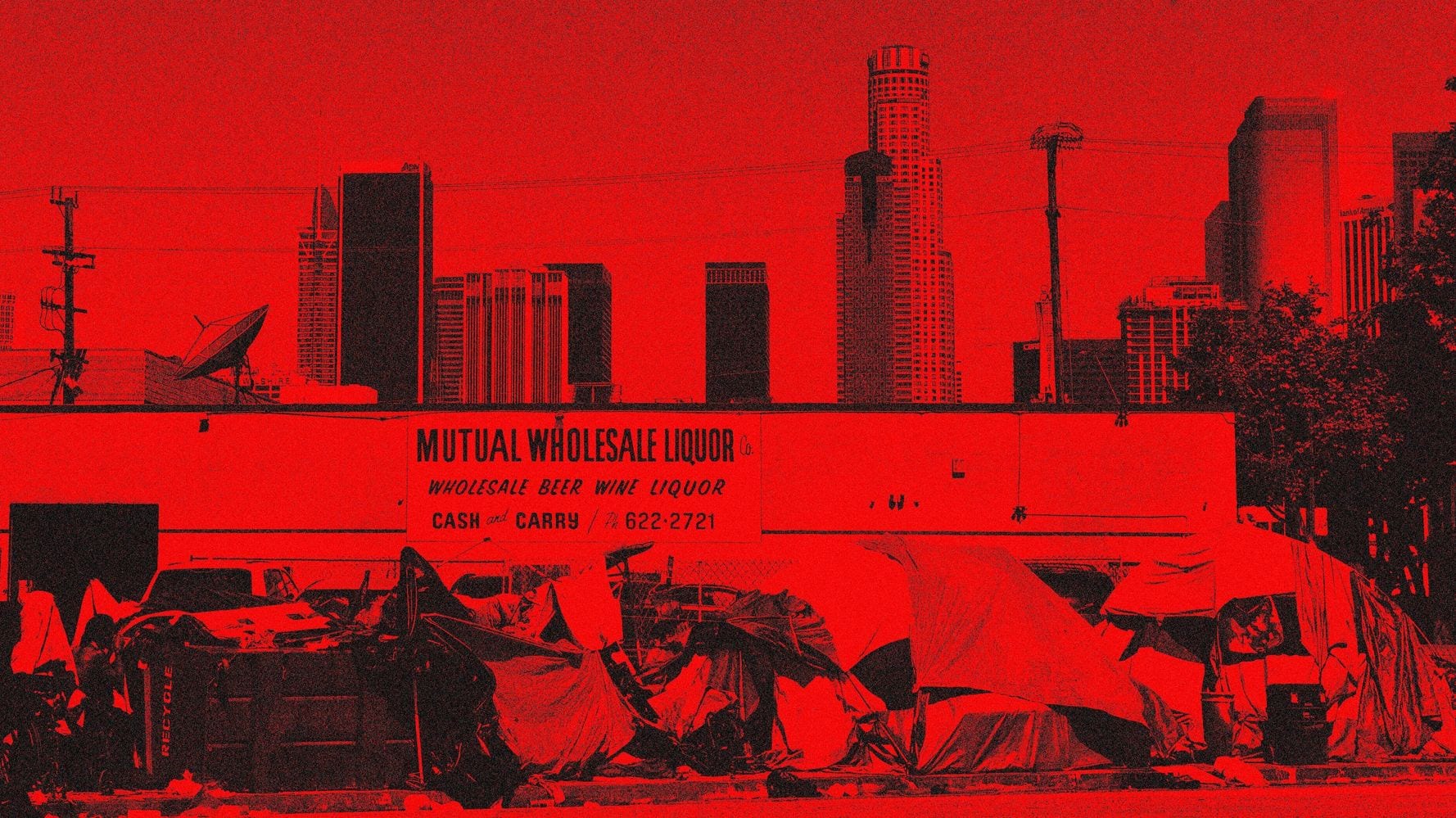

A wave of evictions post-quarantine will mean many cities will see a significant increase in homelessness. In Seattle, a 2017 survey found that the majority of evicted renters ended up homeless. In New York, a 2018 study found that tenants who had experienced an eviction were more likely to move into a homeless shelter — and stay there longer — than tenants who had never been evicted.

“Some people are going to be able to pay their rent with their savings for a few months,” Hatch said. “But if their savings run out and their job still hasn’t come back, a lot of those people are going to end up on the street or scrambling for a new place to live.”

A No-Win Situation

Thousands of newly homeless people and thousands of empty apartments will create a situation that benefits neither renters, landlords nor cities.

Michael Manville, a UCLA professor who studies urban planning, described a scenario in which a renter paying $800 a month loses her job. She can’t pay her rent, gets evicted and ends up moving in with a friend.

If this happens to thousands of other people across the city, landlords may reduce rents to attract new tenants. But, Manville noted, even if the landlord lowered the rent on that apartment to $600, it would be too late for the previous tenant. She wouldn’t have the first month’s rent and deposit needed for a new place and would now have an eviction on her record to deter other landlords from renting to her. Meanwhile, her landlord may not find a new tenant for the apartment for months.

“It’s a collective action problem,” Manville said. “Individual landlords may be confident that if they evict tenants, they’ll be able to fill the vacant unit quickly. If a large number of landlords evict their tenants at the same time, however, there’s going to be too many empty apartments and not enough people with the savings to move into them. All these problems can be avoided by just letting people stay in their homes.”

Only the federal government has the power to keep this problem from spiraling.

Michael Manville, UCLA professor

This scenario would have wide-ranging effects for cities themselves. High vacancy rates make it harder for developers to build new homes because banks won’t want to finance construction in places tenants aren’t paying rent.

The social effects, too, may be long-lasting. Hatch noted that evicted tenants are more likely to lose their jobs, if they’re still employed in the first place. Their children show worse academic performance. They are more likely to move into lower-quality and overcrowded housing, affecting both their short- and long-term health. Even if cities don’t see a significant rise in homelessness, low-income populations may move en masse to cheaper suburbs.

“Renters are being hit hardest and first,” said Jenny Schuetz, a fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program. “These are people without a lot of resources or choices. It’s not clear that when this is over they can move someplace else. They’re going to live wherever they can afford to.”

A Federal Challenge

The severity of the coronavirus-driven housing shock will depend on the steps policymakers take to prevent it.

At the federal level, the National Low Income Housing Coalition is asking Congress to include $100 billion in emergency rental assistance in the next economic stimulus package. This would cover back-rent for tenants so they aren’t evicted as soon as local governments lift the temporary bans. The nonprofit organization is also asking for $70 billion in infrastructure spending to retrofit public housing to help reduce health conditions that make residents more susceptible to COVID-19.

States and cities could also do their part. Gary Painter, the director of the University of Southern California’s Sol Price Center for Social Innovation, said lawmakers could ban rent increases during the pandemic and its economic aftermath. They could also provide low-interest, long-term loans for renters and landlords to cover costs and help renegotiate lease terms, a process that is relatively routine in other parts of the housing market.

“If you own a strip mall and all of a sudden you lose two tenants, it’s not unusual to renegotiate new terms with your financial backers,” Painter said. Cities could extend the same principle to their residential housing by expanding their legal-assistance programs or initiating large-scale negotiations between landlord and renter representatives.

The most important factor in all of these efforts will be keeping Americans in their homes as long as possible. A rise in homelessness is not only a moral catastrophe for cities but also a fiscal one. Nearly every study on the costs of homelessness finds that it is cheaper to prevent evictions than to mitigate their fallout. A 2018 study found that every eviction cost New York City roughly $8,000 in medical care, homeless services and lost wages.

“It makes a lot of sense for the Congress to beef up the money flowing to the typical American, especially lower-income Americans,” Manville said. “Only the federal government has the power to keep this problem from spiraling.”

More Affordable Homes For More People

Saadian noted that the coronavirus should also be a call to reform the policies that made renters so vulnerable to homelessness in the first place.

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, the federal government’s primary vehicle for encouraging affordable housing production, mostly goes to renters who earn around 60% of the local median income. In some cities, households earning as much as $117,400 are eligible for subsidized housing. Attacking the roots of the country’s eviction and homeless crises, Saadian said, will require targeting low-income renters and addressing the federal government’s decades-long underfunding of affordable housing.

“The housing shortage is almost entirely at the low end of the income spectrum,” Saadian said. “If there isn’t sufficient housing at the low end, the problem ends up affecting people higher up the income spectrum.”

The coronavirus may also provide an opportunity for cities to solve the other driver of the housing crisis: the near-impossibility of building more homes in overgrown cities.

“We basically stopped building housing in 2008,” said Jeff Tucker, an economist for real estate listing site Zillow. “We have this huge housing deficit at the same time we have several million extra people in their 30s who are disproportionately renting right now and trying to transition to homeownership.”

If cities don’t address this mismatch, the country could return to its trajectory of soaring home prices relatively quickly after the pandemic is over — or maybe even before. Tucker said that Zillow’s web traffic fell roughly 20% at the start of the pandemic but is now 20% higher than it was last year. “Virtual tours” of homes have increased sevenfold.

Some of this increase is due to Americans having more time to browse real estate listings, but it may also indicate that some potential home buyers, especially affluent ones, plan to use the drop in demand to climb onto the housing ladder. If rents and prices continue to climb as they did before the pandemic, they will only increase the displacement and homelessness risks.

The pandemic should be a call for cities to rethink their economic structures, Schuetz said.

“This crisis makes it clear that housing has implications for our health,” Schuetz said. “We need to keep reminding people that everyone deserves good-quality housing not just for a pandemic but for everything that happens afterward.”

A HuffPost Guide To Coronavirus

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter