[ad_1]

2020-04-15 12:01

South Africans are making great sacrifices during the national lockdown. It is affecting salaries, income, livelihoods and human relationships. We need to understand exactly why we’re doing it, and maximum transparency is critical, writes Nicole Fritz.

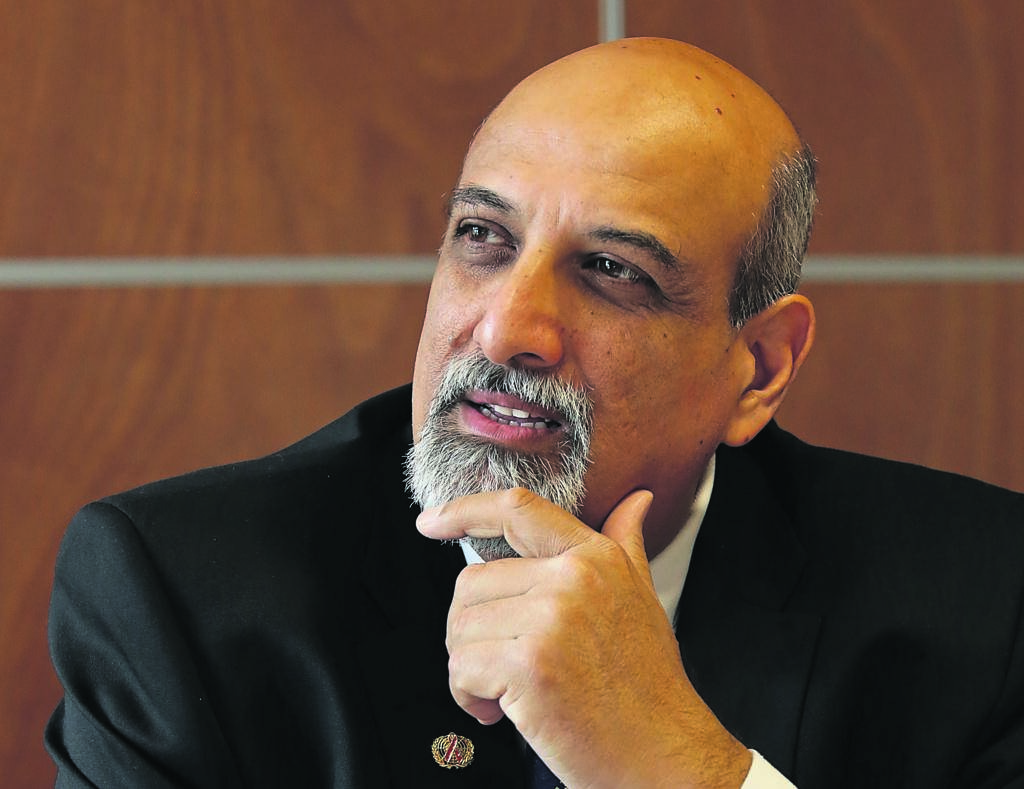

Sunday’s engagement by Health Minister Zweli Mkhize, Dr Salim Abdool Karim and other experts with the South African public is to be greatly welcomed.

While President Cyril Ramaphosa, Mkhize and many others in the executive have rightly earned praise for their leadership during this pandemic, some in the public have become concerned at the failure to provide the hard data, scientific method, modelling, forecasting and analysis that we must presume underlie the many decisions made – from extension of the lockdown to the various regulations.

LIVE | All the latest coronavirus and lockdown updates

Understandably perhaps, given the highly charged and anxiety-inducing times we all inhabit, those of us voicing this concern have occasionally earned fierce opprobrium – said to be insufficiently patriotic, reactionary, callous as to the lives government is saving.

Here are three arguments as to why the concern that there be the greatest possible transparency as to the data and analysis being used is of the most important kind: that this concern is critical – not in the sense of needlessly looking to find fault – but in the sense of being vital.

First, no one can sensibly suggest that the situation we face is not of the gravest kind, but the measures taken by government in response to this pandemic – as with all measures taken by government in normal times too – must find their authority in the Constitution. It is the source of all governmental authority – even in times of emergency. Hallmarks of our Constitution are the requirements of deliberation and justification – requiring participation and deliberation in decision-making and compelling justification from decision makers.

Even the provisions of the Constitution regulating times of emergency uphold the necessity of deliberation and justification. In fact, the drafters of the emergency provisions sought to ensure there was a double-check: not only can any competent court decide on the validity of a state of emergency and any measures taken in consequence thereof, but after the first 21-day declaration of a state of emergency, Parliament’s approval, on the basis of an escalating majority, is required for any further extension. Any extension has to follow public debate in the National Assembly.

Concern for individual dignity

In addressing this pandemic, government has chosen not to utilise the state of emergency provisions, but rather respond using the framework of the Disaster Management Act. As a piece of ordinary legislation, it doesn’t require any extension by Parliament or demand public debate in the National Assembly. Courts can, of course, provide oversight. But in response to the lockdown, heads of court throughout the country have issued directions limiting access to the courts at this time, attenuating the powerful force of this check. In these circumstances, the onus on a responsive government to provide full and detailed justification must be greater not less.

That seems even more true when you consider the nature of the threat we face – not a wartime foe able to use to its advantage information released in the public domain, and so justifying an information blackout, but a pathogen insentient to our data, modelling, projections and analysis.

Second, disclosing the information on which government is relying in responding to the pandemic respects the value of human dignity – a core value of our constitutional democracy. There is lots of debate as to what human dignity entails, but it seems at its essence to at least involve respecting human agency – the ability to plan for and seek to exercise some modicum of control over one’s life, however constrained the circumstances.

Understanding what the models and projections are indicating government’s response should be for the next 12 to 18 months, until such time as an effective vaccine is rolled out or sufficient herd immunity acquired, allows all of us the opportunity to engage in some sort of provisional planning – how best to care for and educate our children for what may be an extended period, how to best protect those we care for who are likely to be especially vulnerable to severe disease. For those more precariously placed, equally deserving of dignity, potential planning might also allow for mitigation of the worst effects of a fast-approaching winter, lack of access to clean water, sanitation and a reliable food supply.

This concern for individual dignity finds echoes in Yuval Noah Harari’s Financial Times article, “The World After Coronavirus”, and his argument for the importance of a scientifically informed population: “When people are told the scientific facts, and when people trust public authorities to tell them these facts, citizens can do the right thing, even without a Big Brother watching over their shoulders. A self-motivated, informed population is usually far more more powerful and effective than a policed, ignorant population.”

No one is setting out to get this wrong

Self-motivation is particularly important considering the types of measures people need to adopt to limit public health emergencies, and the types of measures we will likely need to use to protect ourselves and our communities once lockdown ends. Harari uses the example of hand-washing – an act we are induced to perform because we understand the rational for doing so and not because we are coerced to do so (which, in any event, government would find impossible to do).

Thirdly, the data, modelling, projections and analysis should be shared because that offers us the best chance of getting it right. No question, we are fortunate in having responsible political leadership at this time of crisis. And there is no questioning the calibre of expertise they have assembled.

We can take it as a safe bet that no one is setting out to get this wrong. But Covid-19 has taken the world by surprise and the pandemic is evolving. While countries in the northern hemisphere are giving us some idea of what we are to expect, we also understand that our trajectories – both transmission of infections and consequences of the lockdown – will be particular to our country. Moreover, projections and analysis must necessarily involve collation and coordination of such varied sectoral and geographical expertise that it is hard to imagine why one wouldn’t invite as much scrutiny and interrogation of this exercise as is possible.

Of course there are risks in sharing this information. It may be distorted and manipulated and used to propagate fake news. But we already have in place regulations imposing severe penalties for that type of deceit. And government can wield its full enforcement powers when it has full justification for doing so.

Another risk is that complex models involving multiple, even changing assumptions, could mean that some individuals come to believe that they need not obey instructions. But that’s a risk faced, possibly amplified, when no solid basis for laws and regulations is provided. Legitimately compelling compliance from the public in their observance of laws and regulations does not require that they agree with the particular laws or regulations – only that sound and reasonable justification has been provided for requiring observance.

We are all being asked to make sacrifice – for the good of ourselves, our families, our neighbours, our country. For some, the sacrifice is not one we would make voluntarily – the loss of reliable income, employment, a business. The only solace: that we know that for which we are making sacrifice. But without full disclosure, we can’t even really know that.

** Nicole Fritz is the CEO of Freedom under law.