[ad_1]

Ekurhuleni Mayor Mzwandile Masina announced on 18 March the City was procuring a coronavirus vaccine from Cuba using municipal emergency funds.

The funds could have been used for preventative measures such as providing masks and hand sanitisers or bleach to people in informal settlements to reduce the spread of Covid-19 – but Masina decided otherwise.

LIVE | All the latest coronavirus and lockdown updates

According to an article published by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism last month, no approved vaccine for the coronavirus exists yet.

The “vaccine” Masina referred to was a drug called interferon-alfa-2B which is manufactured by a joint Cuban-Chinese company called ChangHeber.

Interferon shows some promise as a treatment and has been included in a World Health Organisation global trial of the four most promising coronavirus treatments.

Meanwhile, in Langaville Extension 8, Tsakane, Johannesburg, residents line up to use a communal tap that three streets share.

And, on average, about five families share one mobile chemical toilet which is cleaned and drained once a week.

Amid the highly contagious coronavirus pandemic, and with the country on lockdown, fear and anxiety have gripped the residents of Langaville and other informal settlements around Ekurhuleni that amaBhungane visited.

Residents told amaBhungane they wanted to comply with President Cyril Ramaphosa’s call to stay home, but their poor living conditions prevented them from doing so.

“We understand the seriousness of the matter. It is between life and death, but what can we do? One infection here and we are as good as dead.

“How are we to practice washing hands, staying indoors and following a safe distance under these circumstances?” asked one of the community leaders, Makhosini Nhlapo.

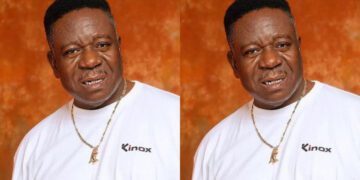

Makhosini Nhlapo. (Tabelo Timse, amaBhungane)

In another informal settlement called Lindelani, sections L and M residents still use the pit toilet system and depend on the municipality to send water tankers.

The community complained the tankers arrived only once a day and there was no set time of delivery:

“People keep an eye on it,” said a resident.

Meanwhile, workers hired to clean the toilets complained that in the absence of protective gear, they too felt vulnerable.

According to the tender specifications for the 2019 contract, successful bidders were required to provide the toilet cleaners with protective gear, such as a pair of safety boots, safety goggles, a set of overalls, rain suit with a hood and reflective strips, elbow-length PVC gloves, respirator masks and anti-bacterial skin cleaner.

However, some of the cleaners whom amaBhungane interviewed said only a few contractors provided basic protective clothing such as overalls, dust masks and gloves, while other workers were not provided with anything at all.

The protective gear is now crucial as a preventative measure against contracting Covid-19.

Communities living in these informal settlements have been calling on Masina’s administration to provide permanent water and sanitation solutions, but it appears their pleas have fallen on deaf ears.

During Masina’s “pro-poor” state of the city address, amaBhungane was conducting interviews in Langaville, where about 10 residents had gathered inside one shack to listen to him.

Of particular interest to them were the municipality’s plans to minimise the spread of Covid-19, especially in informal settlements.

But residents were left disappointed although Masina mentioned the controversial mobile chemical toilet issue in a sentence.

“We will, however, soon start exploring sustainable alternative sanitation technologies,” he said in his speech.

This means that, after years of investing more than R1 billion in the mobile plastic toilets – structures the municipality does not own – only now is the administration investigating other options.

Residents of Langaville have been experiencing toilet problems for four years.

There are almost 800 shacks and 180 toilets, according to the community’s list, which amaBhungane has seen.

A dirty toilet in Langaville Extension 8. (Tabelo Timse, amaBhungane)

In 2016, the City of Ekurhuleni promised residents 39 112 mobile toilets for informal areas around the city.

A three-year tender worth R1.9 billion went out and 16 companies received contracts to supply the new equipment, at an average cost of R300 per toilet per week.

In July last year, amaBhungane reported on the contract.

Critics dubbed the tender Imoto Entshontsha Imali (the vehicle for stealing the money or the getaway car) – suggesting that the project was a get-rich-quick scheme for some underperforming contractors that left many beneficiaries with dirty and broken toilets.

The article also raised questions about flawed tender processes, a lack of oversight from municipal officials and companies taking advantage of municipal incompetence to make a quick buck.

According to municipal statistics from 2018, Ekurhuleni has 119 informal settlements, inhabited by 164 699 households, with about five households sharing one toilet on average.

Despite the allegations about the first contract – and ignoring pleas for more permanent solutions – the City issued a new three-year tender for mobile toilets last year.

As our accompanying story, [Ekurhuleni toilet tender 2.0: same old s**t?] demonstrates, the new awards raise some of the same questions that dogged the old tender.

And now the coronavirus is highlighting the cost residents have to pay when municipalities fail to deliver at this most basic level.

The amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism, an independent non-profit, produced this story. Like it? Be an amaB Supporterto help us do more. Sign up for our newsletterand WhatsApp alertsto get more.

– Stay healthy and entertained during the national lockdown. Sign up for our Lockdown Living newsletter. Register and manage your newsletters in the new News24 app by clicking on the Profile tab