[ad_1]

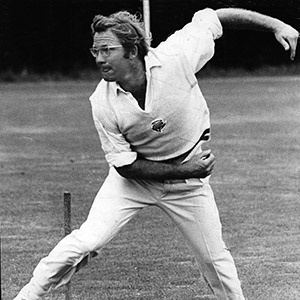

Eddie Barlow made his Test debut for South Africa some two and a half years before I was born, against New Zealand at Kingsmead in December 1961.

I was still only five when his 30th Test – immediately ahead of the country’s apartheid-caused, deep isolation years – would also prove his last: a cherry-on-top triumph over Australia at St George’s Park to clinch the famous 4-0 sweep of 1969/70, Barlow as a team talisman and deputy leader to Ali Bacher.

So I thank my lucky stars that he had the energy and enthusiasm to stay playing the game at first-class level until well into his early forties in 1982/83, where he was veteran captain of an emerging Boland team at the charming Stellenbosch Farmers’ Winery Field in Stellenbosch, a place where sixes could land with a woody thunk on wine barrels and the lunches were sumptuous.

It was more than enough time, even if considerably beyond his all-rounder heyday, for me to splendidly appreciate – first as pure, ever-mounting admirer, then as a rookie scribe – the quite uniquely daring, charismatic and ultra-competitive stamp he put on the game.

His reaction time unavoidably slower but his bellicosity entirely undimmed, I’ll never forget Barlow laying down the gauntlet, in that swansong personal season, at the traditional dinner where the SA Schools XI would always be named after annual then-Nuffield Week.

Knowing that his Boland side were to be playing the schoolboys within 48 hours, he challenged them, with typical charisma: “You boys know I’m (not the youngest) … you are going to try to bounce me in the game, aren’t you? Well, let me tell you now, I WILL hook you!”

Acceptance of the red rag was inevitable, of course, and I am 90 percent sure it was Bishops’ sharp Dave Norman, later of both Western Province and Natal, who duly dug one in short against Barlow (still defiantly in his trademark berth at the front of the order and less than the athlete of his youth).

But the surface at the SFW Field tended toward notoriously benign and yes, even though the coach-manual-defying, brazen uppercut over the slips was a more common factor in Barlow’s stroke-playing repertoire, the grandmaster crisply pulled Norman’s attempted nose-tickler to the pickets with savage glee.

That was Barlow: life-long – until his passing after a stroke on the Channel Island of Jersey in 2005, aged 65 – blessed with an insatiable appetite for a good scrap.

No handouts or favours if you were a foe, regardless of your name, age or team badge.

The word “ebullient” would be latched to him in a media capacity for much of his career, to the point of cliché.

But it was understandable; he hated it when cricket matches went periodically quiet or drifted toward stalemate mode.

That would often be the catalyst for Barlow, whether captain or not, to provide the injection; to dramatically alter the tempo.

If in the field, it would frequently translate into him, possibly exasperated, grabbing the ball and doing his utmost – with an array of medium-pace variations to wow the most cunning of current, white-ball mix-it-uppers – to break a partnership.

Bacher reminds in his book “Ali: The life of Ali Bacher” (with Rodney Hartman, Penguin) of the time during the immortal series against the Aussies when Barlow could not take the visitors’ stubbornness at the crease for a protracted period any longer.

Knuckling down stoically in their follow-on innings of the second Test in Durban, Bill Lawry’s team were giving themselves a glimmer of hope of saving the contest.

Hartman wrote: “It was during the course of the afternoon on the fourth day, with the Australian batsmen grinding out what was shaping as a biggish total, that Ali was unexpectedly handed a telegram.

“It was from Barlow, and it read: PLEASE DOC, GIVE ME A BOWL! This was an offer too unique to resist, so with the total 264 for five and the new ball just 10 overs old, Ali tossed it to the telegram-sender … eleven balls later, Australia were 268 for eight.”

Barlow was skipper of a Western Province Currie Cup team in the mid-1970s, still quite heavily in the amateur era, renowned for a combination of hard-nosed cricket from an array of beguiling characters but also for the fact that, it is often said, some individuals’ “training” was more lustily done in the Long Room at Newlands or (even more dubiously) the nearby Foresters Arms.

Their leader had a rather more eye-on-the-ball adherence to fitness, however, and would occasionally see a need to take the troops on fatiguing mountainside runs.

Another integral member of the WP side of that era, the late Hylton Ackerman, told me at his Marina da Gama home in a nostalgia-oozing interview many years ago of a day when Barlow got wind of the likelihood that wicketkeeper Gavin Pfuhl – who had called in “indisposed” immediately after his workday for one of those ill-liked, impromptu marathons and quite possibly contemplating a sundowner beverage instead – was deviously shirking.

“Well, our team run took an unexpected turn,” Ackerman reminisced.

“We jogged with a special briskness to Gavin’s residence, Edgar John Barlow (Ackerman’s endearing, ever-staple method of noting his reverence for a co-cricketer – Sport24) creaking open the front gate.

“He led us past Prudence Pfuhl’s beautiful rhododendrons, around the edge of the hydrangeas and through the front door. Gavin was scooped up in the whirlwind, with little regard for his state of unpreparedness for the run, and latched onto the group … we all exited the house and continued on our way. The running squad was complete.”

As much as he could be an unforgiving taskmaster when he felt the situation warranted it, another strong Barlow quality was his preparedness to gamble with formulas some might have deemed close to kookoo … nor to be discouraged, even if they bombed spectacularly.

I recall a Newlands match in the then-Gillette Cup (or possibly its reincarnation as Datsun Shield) limited-overs competition against coastal rivals Eastern Province where, despite Marc Mentis making his List-A debut and what would be lone appearance, Barlow chose to “surprise” the visitors by opening the batting with Mentis and, rather than himself as an experienced foil, the happy-go-lucky tail-end hitter and more renowned leg-spinner Denys Hobson: Western Province were pretty quickly nought for two, both individuals back in the pavilion.

Fittingly, too, Barlow had been at the helm of WP in one of the all-time classic Currie Cup matches, something I recollected in an obituary on this website to another iconic figure, Clive Rice, on his passing in 2015, which indirectly contained tribute elements to Barlow as well:

“At the height of his powers, Rice was responsible for perhaps the seminal moment in Currie Cup cricket history when, in the advanced shadows of the final day of the 1976/77 New Year clash there, he bowled then-rookie WP wicketkeeper Rob Drummond with the last ball of a pulsating contest, for which the SABC delayed the 19:00 English radio news to accommodate live commentary until 19:03.

“Under that marvellous gambler Barlow, WP had elected to thrillingly hunt down a seemingly impossible target of 252 in precious little time to win, and the great irony was that come that delivery, they’d finally decided to shut up shop for the intended, honourable draw at 247 for nine after a mighty go at the requirement.

“It was understandably felt that it was asking too much for UCT novice Drummond to smash Rice — already a highly revered bowling “finisher” – for six, so the medical student played a textbook forward defensive stroke … only for the wily ‘Vaal scrapper to get one through the gate and rattle his timber for an immortal away win.”

Bitter though that outcome would have been, Barlow was never going to deviate from rock-solid personal principle: Who dares wins, and sometimes might fail.

He dabbled in both pig- and wine-farming during and/or after his playing career, with varying levels of success, and also ran for parliament once for the anti-apartheid former Progressive Federal Party (PFP), though losing the Simonstown/Fish Hoek by-election to the National Party’s incumbent.

Eddie Barlow was taken from this world cruelly sooner than he deserved to be, particularly considering that effervescence that had seemed so uncontainable.

But I am secretly pleased, thinking about it right now, he didn’t have to get through a modern coronavirus lockdown.

Sitting on the bum would have driven him to distraction.

That simply wasn’t his style.

Thanks for the great memories, Bunter, even though mine were largely from your twilight … still a very, very good result.

*Follow our chief writer on Twitter: @RobHouwing