[ad_1]

“[The] whole idea of voter fraud is predicated on this idea that greater participation is dangerous and not good for democracy,” Williamson said in an interview with Prism. Williamson pointed to “some of the conservative infrastructure that’s been built to foment this mythical claim of voter fraud and specifically [the] legal and policy organizations that essentially fabricate a problem that doesn’t exist.”

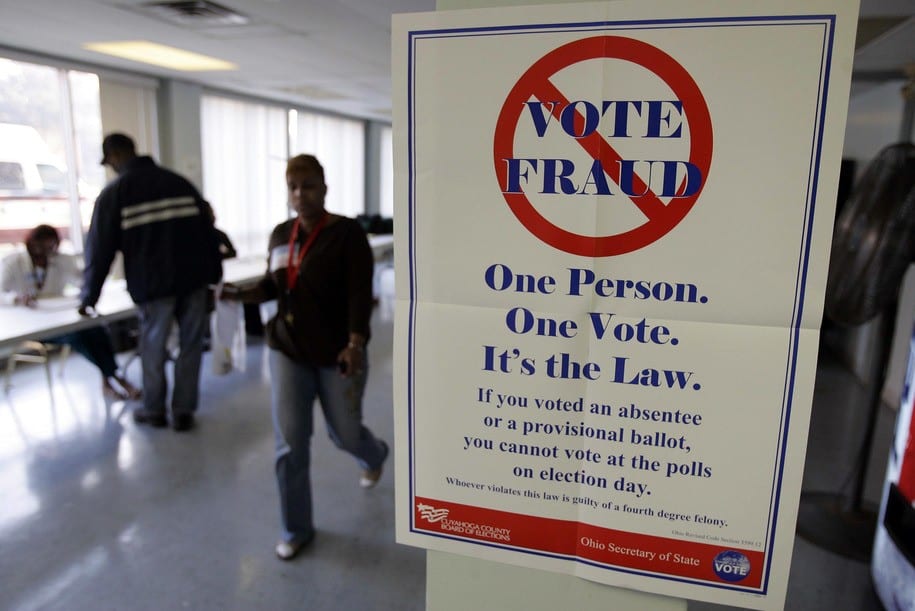

Voter fraud claims distract from competent election administration and integrity

There is a long history of fear-mongering about voter fraud. Similar to yelling “fire” in a crowded theater, cries of “voter fraud” lead to panic and confusion about the safety and integrity of elections.

In a February story from NPR affiliate KUOW, Washington Secretary of State Kim Wyman dismissed claims that it was easy to commit fraud under Washington state’s all-mail system, citing the signature requirement. Speculation of increased issues is not a valid reason for taking drastic actions.

“This isn’t about who wins and who loses,” said Wyman during a panel discussion led by Represent.Us. “The thing that gets left out of the discussion, usually, from people on my side is the security that you have to build in to balance out that access.”

As Wyman pointed out, building in security measures as a part of the process of scaling up absentee ballot use or adopting a vote-by-mail system is crucial.

“I’m an election administrator, first and foremost,” said Wyman. “It always comes first and we can’t make policies based on what’s going to help our party or hurt the other party. When we do that, [it’s dangerous] for both sides.”

Instead of feeding into unsubstantiated claims of voter or absentee ballot fraud, states should be looking to all-mail ballot states and the Election Assistance Commission for tips and assistance in providing secure yet accessible processes, such as having risk limiting audits and other means of verification.

Earlier this year, several conservative groups and strategists convened to discuss a 2020 election strategy that includes aggressive poll watching. As initially reported by The Intercept, two speakers claimed fraud was happening in inner city and tribal precincts and advocated for targeting these communities with their poll-watching effort. Instead of working in a cooperative bipartisan fashion, conservative groups like True the Vote create an increasingly hostile environment with calls for former law enforcement, paramilitary, and others to become poll watchers.

Discussing the broader implications of such tactics, Lauren Groh-Wargo, CEO of Fair Fight Action, stressed the need to also pay attention to how conservatives are operationalizing digital content through paid advertisements and organic posts. The potential spread of disinformation around guarding against so-called voter fraud could also have a chilling effect from folks seeing ads or posts about veterans and law enforcement officials at polling locations in these communities.

“I just think it’s so important to understand, it’s not just for the work they’re doing directly to intimidate, it’s for the work they do to make this a central issue to their party,” said Groh-Wargo. “So that they can operationalize a voter intimidation network in the fall like we’ve never seen before.”

Both Williamson and Groh-Wargo raised concerns about this tactic considering the expiration of a consent decree dating back to the early 1980s that prevented the Republican National Committee (RNC) from coordinating “ballot security” activities including sending law enforcement to polling locations.

State fraud task forces are a distraction and waste of taxpayer resources

Voter fraud allegations are also used to justify wasting taxpayer funds on investigating and prosecuting alleged fraud where none exists, as a first step instead of investing in measures used in all-mail ballot states which have safe and secure elections.

During an April 1 interview, Georgia House Speaker David Ralston said that scaling up absentee ballot use would invite opportunities for “fraud” and expressed concern about Republican ability to win elections if more people had ballots. Ralston failed to point out an actual incident but spoke in vague terms appealing to the general anxiety around “the wrong people” voting.

“Over the last month, they’ve just been saying the quiet part loud and just saying we don’t want Democrats to vote,” said Meagan Hatcher-Mayes, director of democracy policy for Indivisible. “But in the past, they’ve developed all of these ridiculous conspiracy theories about voter fraud, so that they can pass these overly restrictive voting laws to prevent certain types of people from voting.”

Ralston also insinuated that Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger had excluded state Republican leaders from conversations about moving the March 24 presidential primary, giving the impression of some unfairness. But Ralston failed to explain that Republicans did not have a stake in the March 24 presidential primary since there was only a Democratic primary race on the ballot.

Less than a week after Ralston’s comments, Raffensperger announced the formation of an absentee ballot fraud task force in cooperation with law enforcement.

“Part of what people just need to be aware of is that this is going to be the most fraught election in terms of challenging Black and brown voters and young student voters,” said Groh-Wargo.

Groh-Wargo further expressed concern that simple signature match or ID issues could rise to the level of a criminal investigation or possible charges given this focus on criminalizing versus adopting election security measures that balances access to the ballot.

Earlier this week, Raffensperger announced his newly appointed task force members consisting of mostly prosecutors, one U.S. attorney, and no representation from election officials or advocates from the major counties in Georgia. The task force is also made up of primarily white Republicans. Making unsubstantiated claims of potential widespread fraud with increased absentee ballot use, West Virginia’s secretary of state launched a similar effort coordinating with the FBI and U.S. attorneys.

Groh-Wargo compared the creation of these task forces to the same process to pass. “Now I know they have the same fraud task force moving in West Virginia because we know it’s a pilot project in Georgia, they’re going to start moving it around the country.”

Launching these task forces further perpetuates the myth of widespread fraud issues. Georgia’s recent history using alleged claims of absentee ballot fraud to criminalize and target Black voting rights advocates, voters, and candidates serves as a cautionary tale for the current cycle.

Further, signature match issues have been a source of concern in several jurisdictions where absentee ballots have been tossed at high rates. Part of having a secure process is ensuring voters have a clear process for curing alleged ballot issues in a timely manner. It also shifts the burden from local election administrators having to serve as signature experts.

The reality is that election fraud and voter fraud are not rampant threats within our system of elections. There are neither widespread operations to change the outcome of elections through fraudulent activity nor a large number of cases of individual voters committing fraud. Despite the proven low risk of individual voter fraud, Williamson is concerned about an increase in task forces focused on what is effectively a non-issue, and the risk that creates for voters.

“They are creating punitive bodies to essentially legitimize their fictional claims and criminalizing Black and brown people, for the very act of fulfilling their civic duty or making their voices heard.”