[ad_1]

Image copyright

Reuters

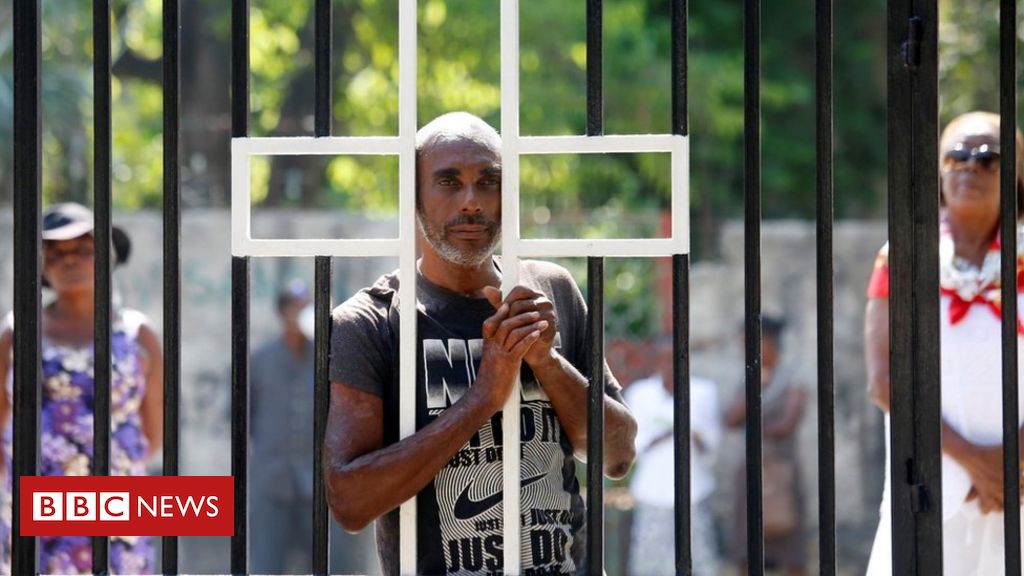

A man stands at the closed gate of a church in Port-au-Prince, Haiti on Easter Sunday

With barely 60 ventilators for 11 million people, Haiti is the most vulnerable nation in the Americas to the coronavirus. While many countries would struggle to cope with a serious spread of Covid-19, Haiti might never recover from one.

The reality inside Haiti’s intensive care units is even bleaker than that number – taken from a 2019 study – suggests. According to Stephan Dragon, a respiratory therapist in the capital, Port-au-Prince, the true number of ventilators is actually closer to 40, and maybe 20 of those aren’t working.

“We also have a very, very limited group of doctors who know how to operate them,” Mr Dragon said.

The Haitian government has recently attempted to buy much-needed equipment – from ventilators to PPE, including tens of thousands of facemasks from Cuba – but Haitian healthcare practitioners like Mr Dragon fear it is too little, too late.

“To tell you the truth, we are not prepared at all,” he said.

So far, this small impoverished nation has only registered three deaths from the virus and 40 confirmed cases, but many more cases may be going unreported, especially in remote areas.

Levels of testing are low and enforcement of social distancing is patchy at best. The Haitian population also suffers high levels of diabetes and other health conditions, and a major coronavirus outbreak would place an unbearable strain on a collapsing healthcare system.

Image copyright

Reuters

Haiti declared a state of emergency in March after two confirmed cases of Covid-19

Haiti’s ability to respond is confounded by its economic straits. Around 60% of Haitians live below the poverty line and many face a stark choice: either go about your daily business and run the risk of contracting COVID-19, or stay indoors, as the government advises, and be unable to put food on the table.

It is little wonder that so many are taking their chances.

That is the dilemma facing Jean Raymond and his family. He lives in Furcy, a mountainous village outside of Port-au-Prince where most families scratch a meagre living from land.

Jean Raymond, however, isn’t a farmer but a motorbike taxi driver, part of Haiti’s vast informal economy. Rremaining indoors is not an option if he is to feed his wife and two young children, he said.

“It’s impossible for me to not leave the house,” he said. “If I’m obligated to stay in my home, what would we eat?”

“It’s impossible for me to not leave the house,” said Jean Raymond, a motorbike taxi driver

Jean Raymond’s wife, Lucienne, criticised the government for failing to show enough support in the village. “We want to respect the rules but we can’t,” she said. “I see what governments are doing in other countries, but here they aren’t doing anything.”

In the absence of the state, it has fallen to local grassroots organisations to carry out basic but vital tasks. Clean water is a precious commodity in Furcy – indeed it is a scarce resource across Haiti – and one environmentalist group called Ekoloji pou Ayiti has prepared dozens of water canisters to make handwashing stations in some of the neediest communities.

Given the deep distrust of NGOs in Haiti, it was crucial to “make sure the community leaders were part of the project,” said Max Faublas, co-founder of Ekoloji pou Ayiti.

As well as building 88 water stations, the group showed people how to make their own hand-sanitiser using vinegar. They have also tried to tackle widespread misinformation with a public education campaign on the importance of wearing a facemask, avoiding handshakes and disinfecting shoes and clothes.

Jean Raymond and his young family washing their hands in Furcy

Still, although members of the community appreciate the rules in theory, putting them into practice can be hard. For example, Jean Raymond and his family live with his parents – six people in a tiny home, all living on top of each other.

And if social distancing is difficult in rural Furcy, it is almost out of the question for many in Haiti’s sprawling, densely-populated shantytowns.

In Port-au-Prince, market days have been cut back, creating further demand for basic food supplies. Some are growing desperate. There have been chaotic scenes outside food distribution points and trucks selling bread. The government has been distributing food parcels to the most vulnerable households but many are angry at having to jostle and compete in a crowd for food.

It has fallen to local grassroots groups to create handwashing stations in communities

“The way they are distributing food is humiliating,” one resident, Mesmin Louigene, told the Reuters news agency. “People do not respect social distancing. The government should organise it better. I’m very concerned at the sanitary conditions, it’s very worrying.”

That the looming healthcare crisis is a great threat to Haiti is of little surprise – that is true of most of Latin America and the Caribbean. What’s especially deadly in the region’s poorest country though is the combination of the pandemic and a crippling economic crisis. In a bid to stave off further economic ruin, the Prime Minister Joseph Jouthe said this week the country’s textile factories would re-open later this month, but the move runs contrary to advice from the Pan American Health Organisation to keep lockdown restrictions in place.

In Furcy, Jean Raymond was under no illusions about what a major COVID-19 outbreak would mean to his village.

“If Coronavirus comes into my community, it would be a disaster. We don’t have a hospital or even a good road. The conditions we live in…” his voice trailed off.

“There’s no way. We will all die if coronavirus comes here.”