[ad_1]

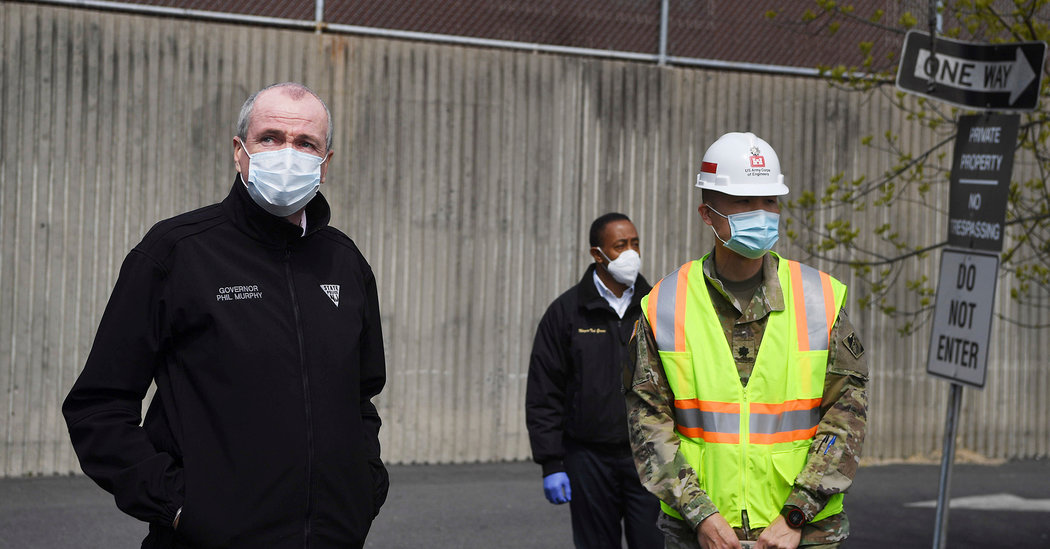

Gov. Philip D. Murphy of New Jersey arrives for his daily media briefings by himself. Clad in a mask, he keeps space between those who walk in before him and sits well beyond the six feet recommended for social distancing.

It may seem like leadership by example, but for Mr. Murphy, it is also a matter of personal survival. It has been seven weeks since news of New Jersey’s first confirmed coronavirus case was delivered to Mr. Murphy while he was on an operating table, about to have a cancerous piece of his kidney removed.

The rapid spread of the coronavirus has forced governors across the country to confront unknowable and seemingly impossible challenges, and few have been more acutely challenged than Mr. Murphy.

Beyond the governor’s personal health concerns, New Jersey has been ravaged by the outbreak, and is second only to New York in both number of cases and deaths, despite ranking 11th in population among the 50 states.

Nursing homes in particular, filled with vulnerable populations and where social distancing between residents and workers is nearly impossible, have been calamitous petri dishes for the disease, and Mr. Murphy has acknowledged the state’s struggle to meet these challenges.

And as the public health crisis appears to be ebbing, some elected officials and top Republicans say Mr. Murphy, who issued his stay-at-home order on March 21, needs to be clearer about how and when he is going to reopen the state.

“It’s important for the governor to convey some sense of hope,” said Jack Ciattarelli, a former Republican state lawmaker and a candidate for governor in 2021. “People are bristling over the lack of discussion as to possibly when and how we relaunch our state economy.”

Jon M. Bramnick, the Republican leader in the Assembly, said Mr. Murphy had been “somewhat resistant” to discussing ending the shutdown.

Still, even his political foes have largely rallied around Mr. Murphy who, as a first-term governor seeking to steady a state that has become an epicenter of the outbreak, has emerged as a different type of Democratic voice.

His briefings — never commanding the limelight that his neighbor, Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo of New York, has attracted — are emblematic of his governing style: deferential yet stoic, present but not overbearing, not likely to draw or seek the spotlight.

The governor’s briefings often stretch beyond 90 minutes or until reporters run out of questions.

Mr. Murphy, 62, doesn’t display Mr. Cuomo’s brashness — his harshest lashings have been to label those flouting stay-at-home orders as “knuckleheads.”

And unlike Democratic governors like Mr. Cuomo or Gov. Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan, Mr. Murphy has often refrained from criticizing President Trump, focusing instead on offering the public gratitude that Mr. Trump often seeks.

“I don’t wake up in the morning with the luxury of picking who my president is that day,” Mr. Murphy said in an interview. “We need all the help we can get from them, and so that doesn’t mean we’re going to pull our punches.”

Mr. Murphy has spoken directly to Mr. Trump about half a dozen times, and the president has publicly praised the governor. “Governor Murphy of New Jersey is a terrific guy and, frankly, he wants — you know, he’s got a pretty hot spot right there,” Mr. Trump said last month.

New Jersey has received 1,050 ventilators from the national stockpile Mr. Trump controls, three field medical stations with 1,000 beds, two Federal Emergency Management Agency field-testing sites and 1.5 million pieces of personal protective equipment, though Mr. Murphy said the state still needed federal help to expand its testing capacity.

“I think his style is well suited to this,” said Heather H. Howard, a professor at Princeton University who served as the chief policy counsel to Jon S. Corzine, the former New Jersey governor. “New Jersey, my sense is, is ready for the steady hand that he provides. It’s not dramatic, but it’s data-driven and thoughtful.”

But even as the death toll and amount of cases climb, Mr. Murphy has clung to evidence, like the declining number of people on ventilators, that the state may be emerging from the worst of the crisis.

Still, the coronavirus continues to stalk nursing homes — more than 40 percent of the state’s deaths have come from long-term-care facilities. Many families of victims said they were never told that the virus had been spreading.

The governor has criticized some of the facilities — he called the deaths of at least 70 people at a nursing home in Andover “not just outrageous, but unacceptable” — while also cautioning about difficulty of protecting long-term-care residences.

“We knew this was going to be a challenge,” Mr. Murphy said. “I have to say, I don’t think in America, let alone in New Jersey, we knew the extent of that challenge.”

For much of his first three years as governor, Mr. Murphy has rarely captured public attention like his Republican predecessor, Chris Christie.

His folksy, aw-shucks exuberance never quite resonated with the blunt Jersey attitude, and his relentless pursuit of progressive policies sowed deep divisions with more moderate leaders from his own party.

Even as he neared the halfway point in office, about 20 percent of state voters still had not formed an opinion about his leadership.

Now his daily briefings attract thousands of viewers on YouTube, and a recent Monmouth University poll found that 71 percent of voters approved of his job as governor — a level of support that nears Mr. Christie’s popularity after Hurricane Sandy rolled over New Jersey.

Even some decisions that have provoked criticism, such as his decision to close state and county parks while neighboring states did not, are widely supported in the state. (Roughly 70 percent of voters favor the park closures.)

Facing shortages of nearly every needed resource to fight the virus, Mr. Murphy has had to get creative. New Jersey recently became the first state to begin issuing temporary licenses to allow foreign-licensed doctors to practice.

In March, he ordered nonmedical facilities to conduct an inventory of personal protective equipment, and this month he directed the State Police to confiscate what was needed.

He sends hundreds of texts a day, with at least one of his two phones constantly connected to a charger, triaging requests from hospital executives with pleas to the White House for more equipment.

“When I tested positive, I was getting text messages and calls two to three times a day, both asking about me and what can he do to help,” said Michael Maron, the president of Holy Name Medical Center, a hospital in Bergen County that was besieged by coronavirus cases.

Mr. Murphy has faced steeper hurdles when it comes to testing.

As late as mid-March, the state had only two test kits from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which were capable of testing less than 500 people total.

Pleas for more testing were rebuffed, even as the outbreak was growing in northern New Jersey. And not until recently were state health officials keeping track of tests performed by commercial labs.

Though testing has picked up in New Jersey, it is still hindered by bottlenecks, like overloaded labs, a lack of materials and the need to occasionally fly tests to other states. Mr. Murphy and other health officials have said that widespread testing is crucial to easing stay-at-home orders.

”The country was completely unprepared as it relates to testing,” he said, while extolling what New Jersey has done. “We’ve gone from zero to 70 sites.”

Though his style may differ, Mr. Murphy has often been in sync with Mr. Cuomo about keeping their states under lockdown. The two communicate frequently, with Mr. Murphy’s declarations of new regulations often coming hours after New York’s governor.

But like Mr. Cuomo, Mr. Murphy has been criticized for not moving quickly enough to shut down New Jersey.

Mr. Murphy issued a stay-at-home order on March 21, when there were 1,327 cases; New Jersey was the fourth state to make such a declaration. But California had issued its order two days earlier with half the number of cases.

”One could have argued that it should have been done earlier, because if it was done earlier it would have had more of an impact,” said Brian Strom, the chancellor of Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences.

But, Mr. Strom said, it was a difficult decision because federal guidelines were not calling for a complete shutdown and neighboring states were not taking similar steps. “Could you really expect a New Jersey or New York to say we’re going to shutdown our economy when no one else is?” he said. “We’re shutting our schools when everyone else is open?”

Mr. Murphy said he calibrated the shutdown with the role that institutions play in providing a social safety net. Schools, for example, needed to be able to deliver distance learning to children who lack access to the internet or the necessary devices.

“For kids who rely on their schools for their only hot meal or remote-learning concerns,” Mr. Murphy said, “I was prepared to let that go a couple of days to make sure the plan was the right one.”

As his briefings have grown more grim — with daily deaths in the hundreds — Mr. Murphy has began sharing the life stories of a handful of those who have died. There was Margit Feldman, 90, a Holocaust survivor; Richard Campbell, a 28-year veteran firefighter and chief of the Edison Fire Department; and Darrell Johnson, 43, who worked at Morristown High School.

Mr. Murphy began these daily tributes on March 30, hoping they would bring some solace to those who could not grieve together.

“I call somewhere between, probably, plus or minus a half a dozen families a day and just talk to them,” the governor said. “And the part that really sucks for these families, in addition that they lost somebody, is they can’t have a normal farewell. They can’t have a wake or a funeral. And I think it came out of that, to say, you know what, at least for a handful of people each day, let’s put them up in lights.”