[ad_1]

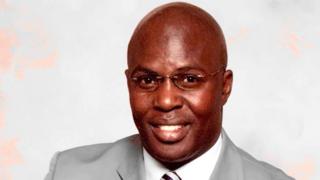

Image copyright

Hezekiel Gikambi

The Kenyan author Ken Walibora who was buried last week left behind a generation of fans who read his books in Swahili classes, including the BBC’s Basillioh Mutahi.

Prof Walibora was renowned for promoting Swahili, the national language he used in writing his books.

In 2018 he expressed concern that some schools in Kenya had notices reading: “This is an English-speaking zone”.

He asked the ministry of education why it would allow students to be barred from speaking in Swahili, when it was a national language.

The author said this was a sign of brainwashing and neo-colonialism. You would not find another country that would choose a foreign language over the language of its people, he said.

GETTY

-

50 to 100 million estimated speakers

-

Arabichas lent many words – including Swahili, Arabic for coast

-

Fourcountries speak it most: DR Congo, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda

-

African Unionhas adopted it as one of six official languages

-

Written Swahiliused to use Arabic script before switching to Latin alphabet

Source: Culture Trip

His most prominent book was his first novel Siku Njema which was later translated to English as A Good Day. It was used as a set book in high schools around the country for many years.

Many Kenyans who read it in school have spoken about how the novel, a tale of triumph over adversity, helped them love Swahili literature – which is something Kenyans often find difficult to do.

Our neighbours in Tanzania are supposed to be the most proficient speakers of this language used as a lingua franca by around 100 million people across East Africa.

Prolific writer

Prof Austin Bukenya, one of the pioneering African scholars of English and literature in East Africa, from Uganda, argued that Prof Walibora was the “king” of Kenyan Swahili literature.

Who was Ken Walibora?

- Born on 6 January 1965 as Kennedy Waliaula in Baraki, Bungoma county, in western Kenya

- Later changed his identity to Walibora, the latter part of his surname which means “better” in Swahili. He also shortened his first name to Ken

- Worked as a teacher and a probation officer before he became a journalist. He has also served as a professor of the Kiswahili language in the US and Kenya

- Died on 10 April after he was hit by a bus in downtown Nairobi, the police initially reported

- He had been reported missing for five days when his body was found at the mortuary of Kenya’s main referral hospital, the Kenyatta National Hospital

- The police’s homicide department have since taken over investigations into his death after a post-mortem by the government pathologist revealed he had a knife wound on the space between his thumb and the index finger

- Buried on 21 April at his home in western Kenya in a funeral attended by not more than 15 people, due to the regulations imposed to stop the spread of coronavirus

- His widow and two children did not attend as they could not leave the US, where they live, due to Covid-19 travel restrictions

Image copyright

Unknown

Only 15 people were allowed to attend his funeral in an effort to prevent the spread of coronavirus

He was a prolific writer- between 1996, when Siku Njema was published, and the day he died, he had more than 40 books to his name in varied genres – novels, short stories, plays and poetry.

He has been described as a man who was always writing, and writing best sellers. Even towards his unforeseen death, he had at least one book that was nearly ready, which is now due to be published posthumously.

Other than Prof Walibora’s debut novel, he had another novel that was read as a national set book for Kiswahili literature in schools, Kidagaa Kimemwozea.

But it was that first book, Siku Njema, that really endeared him to young readers. I was one of them. I wanted to become the writer that he was, as well as the fictional main character who was almost like a role model.

Aspirational story-telling

I remember reading that book, with a cover illustration of a silhouetted man looking into the distance, in just one evening about 20 years ago, on the day it was issued in class as our high school literature text.

In the two years that followed, we would explore it in detail, studying the themes, stylistic devices and all.

But what resonated most with me was the aspirational aspect of his story-telling, which almost inspired you to see the possibilities to do better not just in school, but in life.

Re-reading Siku Njema reminded me how much of an impact Walibora had on my life

But other than the analogies of hope that I identified with, I found it an easy read, with its vivid imagery and poetic language.

I identified with the struggles of the book’s main character, Msanifu Kombo, an ill-treated child who grew up without his parents, and who later took on a perilous journey from Tanzania to find his father in Kenya.

In the book, Msanifu Kombo is a brilliant student of the Swahili language, at one point taking the prize for an essay he wrote for a school competition. His schoolmates nickname him Kongowea Mswahili, the name of the key character in his prize-winning essay.

Like Mswahili, I came to love Swahili in school, which inspired me to write a manuscript in Swahili of my own – which I have kept ever since.

And I immersed myself into learning more of the language, which helped me earn top grades in the language for the rest of my high school life. I was also nicknamed Kongowea Mswahili.

Working with my hero

Later in life, our paths crossed at the Nation Media Group in Nairobi, where we both worked as journalists.

In a way, I was proud to be working with a man, who in my teenage years, was my hero.

Though we were both journalists now, seeing him as a hero never really went away, as he was this man who kept on writing books – catching up with him seemed an unachievable goal.

Yet I was often struck by the realisation that his personality was different from the person I imagined he was, many years earlier. He was an ordinary man who easily struck up conversations with colleagues despite his fame.

Looking back, that feeling of wanting to be a writer like him has lingered on, but in the business of a newsroom and working for different publications, I never let him know how much he inspired me – something I now regret.

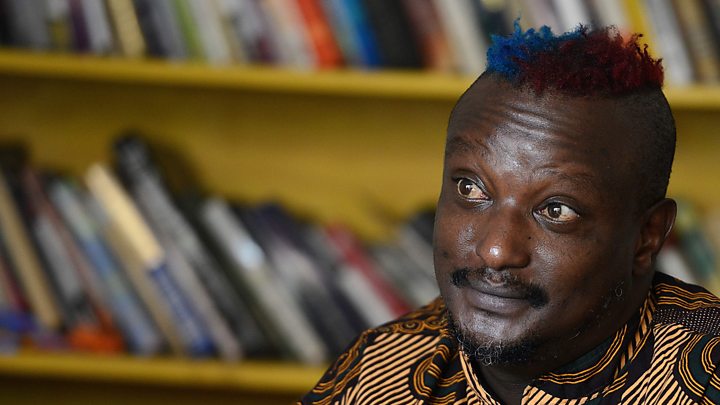

Image copyright

Getty Images

When the announcement of Prof Walibora’s death came, many Kenyans were shocked. Many paid tributes to an author who they had known personally, at work, or though the various books he had written.

Douglas Mutua, a writer and lecturer in the US who was once Prof Walibora’s colleague, remembered the author as a person who nurtured talent. Mr Mutua told the BBC’s Peter Mwai that Prof Walibora loved three things: Swahili, humanity and football.

On Twitter, a Kenyan described Prof Walibora as Kenya’s William Shakespeare. It was an accolade I had never heard, which perhaps he would not have wanted, being a modest person who was never keen to flaunt his envied position as a celebrated author.

“There are people who are worth remembering and who can be remembered, but I’m not one of them, I’m not among them,” he wrote in his introduction to his autobiography Nasikia Sauti Ya Mama (I Hear My Mother’s Voice).

“If by writing this [autobiography] I will have shown an example of how to write an autobiography, and not an example how to live a life, then I will have achieved my goal,” he added.

You may also be interested in…

BBC Africa staff read extracts from Binyavanga Wainaina’s famous satirical essay How to Write about Africa, in tribute to the late writer.

Media playback is unsupported on your device