[ad_1]

Good morning and welcome to On Politics, a daily political analysis of the 2020 elections based on reporting by New York Times journalists.

Sign up here to get On Politics in your inbox every weekday.

Where things stand

-

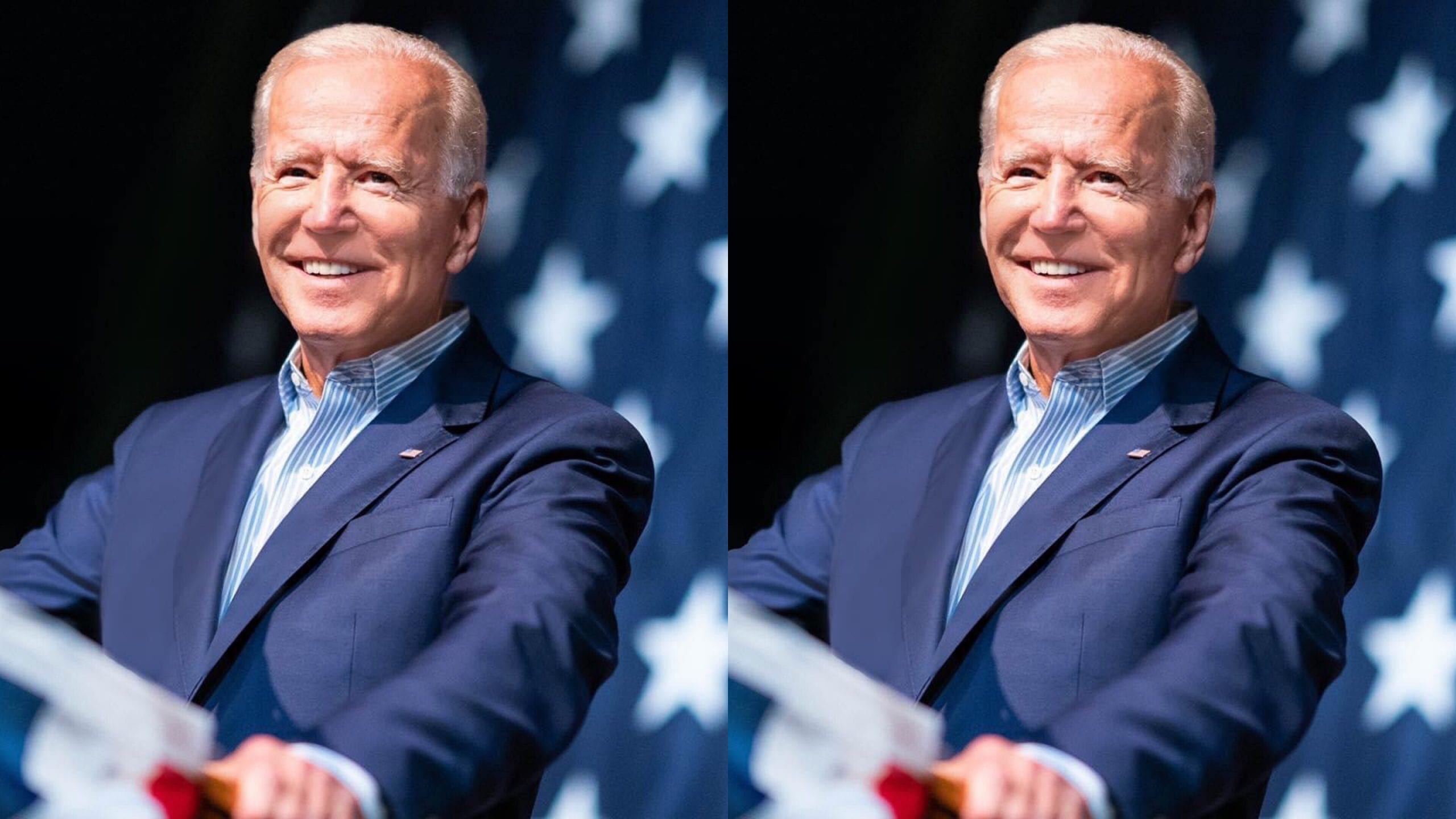

Maybe you’ve noticed a trend in the high-profile endorsements of Joe Biden rolling out this week. Speaking alongside Senator Bernie Sanders on Monday via a joint live stream, Biden picked up a line of argument that his vanquished Democratic challenger had often used against him. “We just can’t think about building back to the way things were before,” Biden said. “That is not good enough. We need to build for a better future.” The next day, throwing his weight behind Biden in his own video address, former President Barack Obama echoed that argument. “If I were running today, I wouldn’t run the same race or have the same platform as I did in 2008,” he said. “We have to look to the future. Bernie understands that, and Joe understands that.” Think about that for a second: The former president, who led the country until just three years ago and remains very popular among Democrats, is pointing out that even the party’s old approach is no longer enough. Obama acknowledged the need for “real structural change,” a nod to Senator Elizabeth Warren’s lexicon. When Sanders announced his endorsement, many activists and organizations on the left that had supported him or Warren were quick to clarify that they expected Biden to offer more concessions before they would line up behind him.

-

It’s no coincidence that Obama’s endorsement came one day after Sanders’s. The former president and the senator have had at least four conversations in recent weeks. Those conversations played a role in Sanders’s decision to quit the presidential race and throw his support behind Biden. In his remarks, Obama pitched his former deputy as a ruler-by-committee, implying that as president, Biden would continue to listen to Sanders’s allies, while also underhandedly tweaking President Trump’s handling of the coronavirus. “I know he’ll surround himself with good people,” Obama said. “Experts, scientists, military officials, who actually know how to run the government — and care about doing a good job running the government.” At the end of his remarks, Obama hit on the theme of teamwork again. “Join us. Join Joe,” he said.

-

Trump backed off his combative stance against the governors who have been formally organizing among themselves in response to the pandemic. On Monday, he had said that the White House had “total” authority to reopen the economy when it wanted. But on Tuesday, the president struck a more accommodating tone, and explained that it made more sense for governors to decide on their own — though he continued to express a dubious interpretation of his own authority. “I will be speaking to all 50 governors very shortly, and I will then be authorizing each individual governor of each individual state to implement a reopening,” Trump said. “We’re counting on the governors to do a great job,” he said.

-

If Trump’s daily briefings during the pandemic have left you wanting to hear from him more, well, you were nearly in luck. Imagine a daily, two-hour radio show hosted from the White House by the president himself: This, Trump told his staff recently, was his dream. It was only Trump’s worry that he would compete with his friend Rush Limbaugh for ratings that tanked the idea, our colleague Elaina Plott reports.

President Trump spoke before reporters and officials practicing social distancing at the daily coronavirus briefing in the Rose Garden of the White House on Tuesday.

Trump is blaming the W.H.O. Here’s the timeline.

As the pandemic holds American life in a headlock, Trump is looking for a narrative that frees him from at least some blame for its spread.

On Tuesday, he turned up the heat on the World Health Organization, saying it had caused “so much death” by discouraging a ban on travel from infected countries. He announced that he would temporarily stop payments to the organization as he criticized its “disastrous decision to oppose travel restrictions from China and other nations.”

The virus was first detected by doctors in Wuhan, China, at the end of December, and the organization’s experts evaluated it for weeks before declaring it a global emergency. After the W.H.O.’s emergency committee convened on Jan. 22 and Jan. 23, its director general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said, “Make no mistake: This is an emergency in China,” but had declined to label it a global health emergency.

The organization eventually did so in an advisory published on Jan. 30, but it did not recommend any restrictions on international travel or trade. The next day, Trump went ahead anyway with banning travel from China, which he now claims saved “thousands and thousands of lives,” but the move might have come too late and included spotty screening. On March 11, Trump extended travel restrictions to include Europe; the W.H.O. labeled the outbreak a pandemic the same day.

Trump was heaping praise on the organization as recently as late February, when he insisted that the virus was “under control” in the United States.

But he is not alone in now criticizing the speed of the W.H.O.’s response. A Change.org petition demanding Ghebreyesus’s resignation has been signed by over 900,000 people.

What Trump rarely acknowledges is that he often played down the virus’s threat, even after the organization labeled it an emergency, and for months, he resisted the advice of members of his own administration to more aggressively confront it.

Trump declined to explain on Tuesday why the White House had not taken more decisive steps during January and February to prepare for the pandemic.

Instead, the president’s darts were pointed squarely at the W.H.O. “Today I’m instructing my administration to halt funding of the World Health Organization while a review is conducted to assess the World Health Organization’s role in considerably mismanaging and covering up the spread of the coronavirus,” he said. “Everybody knows what’s going on there.”

And states continue to report shortages of medical supplies and tests.

On Politics is also available as a newsletter. Sign up here to get it delivered to your inbox.

Is there anything you think we’re missing? Anything you want to see more of? We’d love to hear from you. Email us at onpolitics@nytimes.com.