[ad_1]

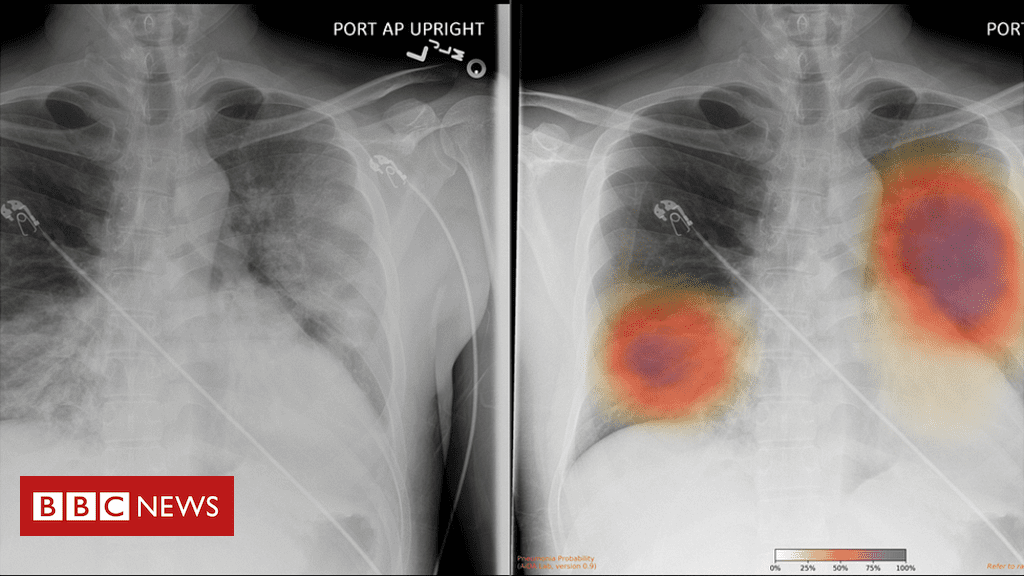

Image copyright

UCSD HEALTH

The coloured area shows where the algorithm has detected pneumonia

When Covid-19 was at its height in China, doctors in the city of Wuhan were able to use artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to scan the lungs of thousands of patients.

The algorithm in question, developed by Axial AI, analyses CT imagery in seconds. It declares, for example, whether a patient has a high risk of viral pneumonia from coronavirus or not.

A consortium of firms developed the AI in response to the coronavirus outbreak. They say it can show whether a patient’s lungs have improved or worsened over time, when more CT scans are done for comparison.

A hospital in Malaysia is now trialling the system and Axial AI has also offered to donate it to the NHS.

Around the world, artificial intelligence (AI) technologies are being rapidly deployed as part of efforts to tackle the coronavirus pandemic. Some question whether these tools are reliable enough, though – after all, people’s lives are at stake.

The BBC has asked the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) to confirm whether Axial AI’s system will be trialled in the UK but has so far not received a response.

A stumbling block for the tool may simply be that the NHS is not commonly using CT scanners to make images of Covid-19 patients’ lungs. Chest X-rays are much more often used instead. They are less detailed than CT scans but are quicker to do and radiologists can still identify, for example, pneumonia in the images.

Image copyright

Qure.ai

Chest X-rays at the Royal Bolton Hospital are now being automatically examined by AI

However, thanks to the pandemic, a few British hospitals are now rolling out AI tools to help medical staff interpret chest X-rays more quickly. For instance, staff at the Royal Bolton Hospital, are using AI that has been trained on more than 11,000 chest X-rays, including around 500 confirmed Covid-19 cases.

It has been running automatically on every chest X-ray the hospital has carried out for about a week, says Rizwan Malik, a radiology consultant at the hospital. This means more than 100 patients will have had X-rays analysed by the system to date, he estimates. In this case, the algorithm is designed to look for possible signs of Covid-19, such as patterns of opacity in the lungs.

“It basically gives clinicians another tool to help them make decisions – for example, which patients they’ll admit, which they’ll send home,” says Dr Malik, who notes that patient data is processed entirely within the hospital’s own network. The software itself was developed by Mumbai-based Qure.ai.

Dr Malik adds that he has provided consultancy services to Qure.ai in the past but stresses that the system went through standard checks and procurement processes before being rolled out at his hospital.

Image copyright

Rizwan Malik

AI “gives clinicians another tool to help them make decisions,” says radiology consultant Rizwan Malik

The BBC understands that two other NHS hospitals are currently using a different tool, which detects abnormalities in lung X-rays. A spokeswoman for Behold.ai, which developed the system, did not name the hospitals involved.

However, she said the software has so far analysed the scans of 147 patients with suspected Covid-19. It correctly classified the scans as “normal” or “abnormal” in more than 90% of cases.

Treating patients with severe lung problems caused by Covid-19 can be distressing, says Dr Thomas Daniels, a respiratory specialist at University Hospital Southampton. He and his colleagues have not yet used an AI algorithm to analyse chest X-rays in Covid-19 patients. However, he says a system that automatically interprets scans so that doctors can digest the information quickly could be useful.

“It often takes a… radiologist hours or sometimes even days to get to that particular chest X-ray and write a report on it,” he says.

“There may be some role for an algorithm to generate a likelihood-of-Covid score. That would obviously be so much quicker to generate than waiting for a radiologist report.”

Image copyright

Thomas Daniels

“There may be some role for an algorithm to generate a likelihood-of-Covid score,” says respiratory specialist Thomas Daniels

However, he cautions that in his view such tools should be properly assessed via randomised trials – for example, where some patient X-rays are analysed by the algorithm alongside others that are not. Data from such experiments can show whether using the tool made a material difference to how patients fared in hospital.

Elsewhere in the world, similar algorithms are chewing over chest scans in clinical settings. Dr Christopher Longhurst says that his hospital, University of California San Diego (UCSD) Health, is trialling software designed to spot pneumonia in chest X-rays.

“It’s really important that we rigorously analyse the outcomes and data,” he says, though he notes that use of the system is not randomised – it is currently being applied to every chest X-ray at the hospital.

An algorithm that interprets X-ray imagery could be used by doctors in a variety of different ways. It might have a strong effect on their decisions about what to do with a patient or it might be a very small, even tangential part of that process. It is worth noting that the American College of Radiology has recommended against relying on chest scans to diagnose Covid-19.

But algorithms may yet have some role to play in the process. At UCSD Health, the tool referred to by Dr Longhurst flagged up an early case of pneumonia in a patient who was having a chest X-ray for other reasons. The patient was then tested for Covid-19 and the result came back positive.

Image copyright

Luke Oakden-Rayner

AI systems need to be formally tested, says Luke Oakden-Rayner from the University of Adelaide

Luke Oaken-Rayner, a radiologist and PhD candidate at the University of Adelaide, says that there are sticky issues with using AI to help make decisions about treating Covid-19 patients. For one thing, he explains, there isn’t yet a universally accepted plan for how to treat severe cases.

AI might give a doctor an overview of a patient’s current condition but as of today that doesn’t necessarily help them decide what to do next. Moreover, there’s a chance that a newly adopted AI system could make the occasional mistake when interpreting images of people’s lungs. What if an inexperienced doctor changes their treatment plan for a patient due to that erroneous information, potentially causing harm?

“It’s a really serious potential risk,” says Dr Oaken-Rayner. He adds that while he thinks hospitals should be free to try out new technologies, he would be wary of relying on any new system before it is properly vetted.

Relaxing regulatory rules to allow new technologies to be trialled quickly in hospital settings is acceptable given the urgency of the current crisis, he argues. However, he adds that what is really needed is the results of randomised trials like those suggested by Dr Daniels – proof, in other words, that AI tools really make a difference for doctors treating Covid-19 patients.

“It wouldn’t be too hard to get evidence at this stage and so far no-one’s presented it,” says Dr Oakden-Rayner.