[ad_1]

WASHINGTON — Last weekend, an anniversary of the kind that would have once united the country in reflection — the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, 25 years ago — passed without much in the way of comment. As the days inside pile up, our usual approach to a national moment of remembrance appeared lost to the fog of time, germs and Trump era news cycles.

The lack of attention was cast in relief by one person who did speak up: Former President Bill Clinton, who for a variety of reasons seems to have receded from public view since his wife was defeated by Donald Trump for the presidency in 2016. Mr. Clinton, the embattled first-term president of early 1995, would become the dominant presence in the brittle aftermath of Oklahoma City. The various psychodramas of his two terms can obscure the significance of the incident as a political marker of that era; now, it is a global pandemic that is seizing attention from Washington traditions like civic remembrance and bipartisan affirmation.

“In many ways, this is the perfect time to remember Oklahoma City and to repeat the promise we made to them in 1995 to all Americans today,” Mr. Clinton said in an op-ed that ran last Sunday in The Oklahoman.

It’s easy to dismiss this as boilerplate pulled straight from the “stuff politicians say” binder. But its tone is also conspicuous in how it contrasts with the words to a nation in need of solace and mending that come from the current White House.

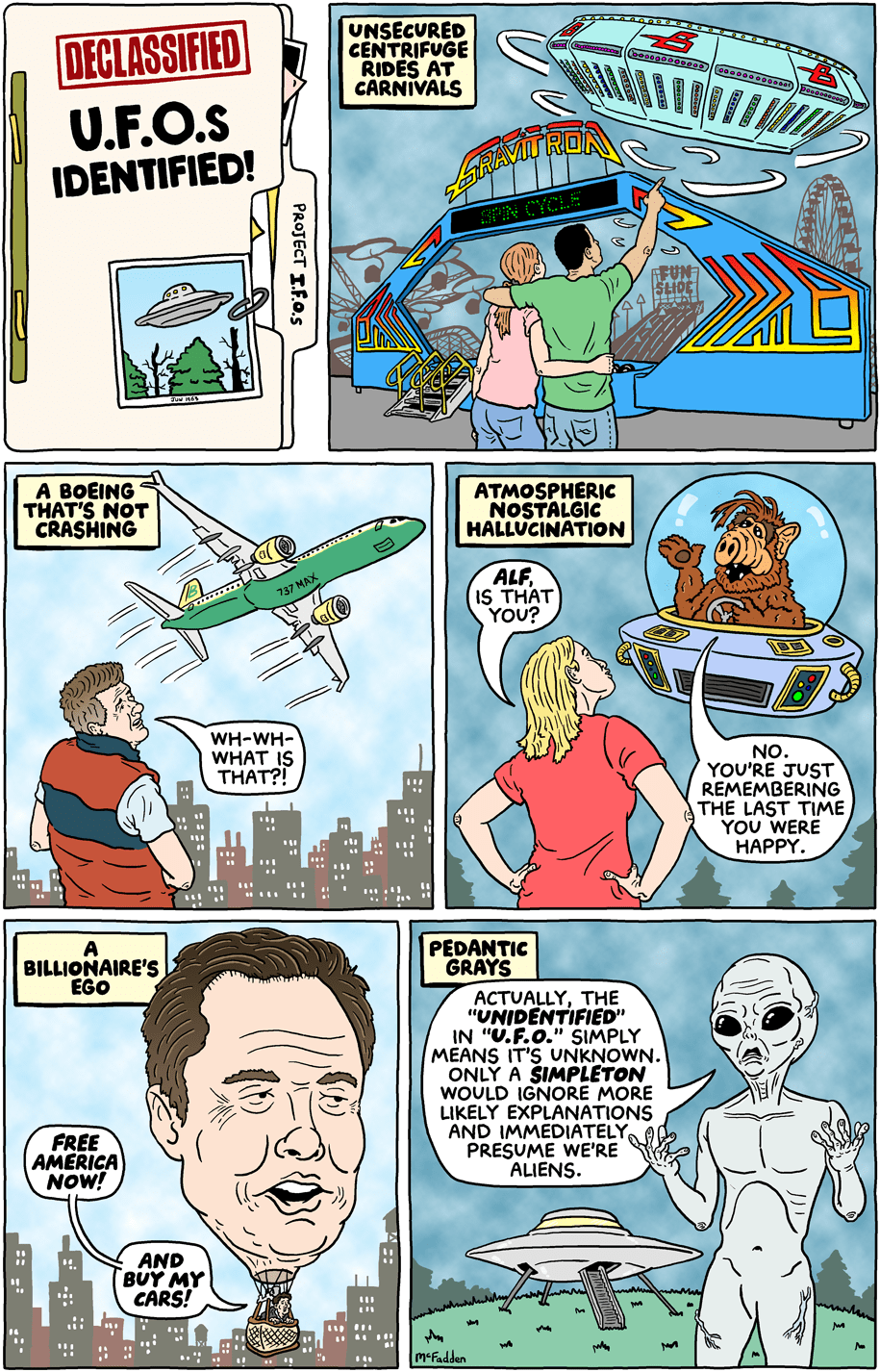

One of the recurring features of the Trump years has been the president’s knack for detonating so many of our powerful shared experiences into us-versus-them grenades. Whether it’s the anniversary of a national catastrophe like the Oklahoma City bombing, the death of a widely admired statesman (Senator John McCain) or a lethal pathogen, Mr. Trump has exhibited minimal interest in the tradition of national strife placing a pause upon the usual smallness of politics.

In this fractured political environment, the president has shown particular zest for identifying symbols that reveal and exacerbate cultural divisions. Kneeling football players, plastic straws and the question of whether a commander in chief should be trumpeting an untested antimalarial drug from the White House briefing room have all become fast identifiers of what team you’re on. Looming sickness and mass death are no exception. The reflex to unite during a period of collective grief feels like another casualty of the current moment.

It used to be a norm, back before everything got stripped down to its noisiest culture war essence. Tradition dictated that whenever a national loss or trauma occurred, political combatants would stand down, at least for a time. President George W. Bush could embrace Senator Tom Daschle, then the Democratic majority leader, after an emotional address that Mr. Bush delivered to a joint session of congress in the days after the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks. President Barack Obama did the same with Chris Christie, the Republican governor of New Jersey, when Mr. Obama visited the state and saw the devastation of Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

To varying degrees, both Mr. Daschle and Mr. Christie caught heat from within their parties after the crises faded into the past and partisan engines revved up again. At the time, though, the gestures felt appropriate and stature-enhancing for everyone involved. Those dynamics have since shifted considerably.

“I think we’re dealing with a whole different world and set of personalities,” said Mr. Daschle, now a former senator from South Dakota, adding that acts of solidarity during adverse times benefit all parties. “I remember after 9/11, congressional approval was something like in the ’80s, and for the president it was around the same,” he said.

Oklahoma City also offered a political gift to Mr. Clinton, a battered leader whose party had lost control of Congress the year before and who had, a few days earlier, found himself defending the “relevance” of his office. Mr. Clinton performed his role of eulogist and comforter, won bipartisan praise for his “performance” and an increase of good will that would eventually help right his presidency on a path to his re-election in 1996.

Mr. Clinton, historians said, always appreciated the power of big, bipartisan gestures, even when they involved incendiary rivals. “He understood the healing powers of the presidency,” said Ted Widmer, a presidential historian at City University of New York, and a former adviser to Mr. Clinton who assisted him in writing his memoirs. He mentioned a generous eulogy that Mr. Clinton delivered for disgraced former President Richard Nixon, after he died in 1994. “There is a basic impulse a president can have for when the country wants their leader to rise above politics and mudslinging,” Mr. Widmer said.

In that regard, Mr. Trump’s performance during this pandemic has been a missed opportunity. “The coronavirus could have been Donald Trump’s finest hour,” Mr. Widmer said. “You really sensed that Americans wanted to be brought together. But now that appears unattainable.”

For whatever reason, Mr. Trump seems uninterested in setting aside personal resentment, even when some small gestures — a photo op or a joint statement with Democratic leaders in Congress; a bipartisan pandemic commission chaired by former presidents — could score him easy statesmanship points.

His unwillingness to deal in any way with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (they have reportedly not spoken since the House voted to impeach Mr. Trump in January) has rendered him a bystander during negotiations with Congress on massive economic recovery bills that were by and large led by Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin. He has taken shots at popular Democratic governors in the hard-hit states of Washington and of Michigan; his approval ratings are dipping — and lag behind that of most governors.

Supporters of Mr. Trump say they appreciate that he doesn’t betray his true feelings for the sake of adhering to Beltway happy talk. This resolve appears central to his credibility with them. They elected him to disrupt, not to play nice and don a mask, whether made of artifice or cloth.

This weekend was supposed to mark another of those pauses in D.C. hostilities, albeit of a very different nature: the annual White House Correspondents’ Dinner, the spring tradition that brings together a hair-sprayed throng along a pecking order of A- to D-list celebrities. The festivities are embedded with the ostensibly high-minded purpose of saluting the First Amendment and raising money for journalism scholarships. If you can score yourself a selfie with Gayle King, all the better.

In the view of many inside the Beltway, the correspondents’ dinner had long outlived its appeal and probably should have been canceled well before Covid-19 did the trick this year (the dinner has been postponed until August). Regardless, presidents of both parties would reliably show up, if only as a gesture of good faith or nod to a local bipartisan tradition.

But Mr. Trump — a veteran of the dinners in his pre-political days, including a memorable evening in which he endured a brutal roasting at the hands of then-President Barack Obama in 2011 — wanted no part of the correspondents’ dinner from the outset of his presidency. Instead, he would take the opportunity to hold “alternative programming” events in the form of Saturday night rallies in places like Pennsylvania, deftly placing himself in populist opposition to the preening Tux-and-Gowned creatures of the swamp.

Mr. Trump’s arrival in Washington inspired another counter-programing surrogate for the main event when the comedian Samantha Bee, host of the TBS program “Full Frontal,” started her own production across town, called “Not the White House Correspondents’ Dinner.” There, she would toss affectionate barbs at the assembled press, usually at the expense of Mr. Trump. “You continue to fact-check the president,” she said in 2017, “as if he might actually someday get embarrassed.”

Beyond the excesses of the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, for a president to partake of this tradition also requires an ability to be a good sport. The guest of honor will inevitably suffer good-natured ribbing at the hands of the hired comedian (or, better yet, not-so-good-natured ribbing — the most memorable routine occurring in 2006, when Stephen Colbert unleashed a sarcastic takedown of then-President George W. Bush and the press corps that Mr. Colbert pointedly suggested had coddled him).

The exercise also requires a president with at least minimal skill at solemnly paying heed to the principles that brought everyone together in the first place. First among these is the preservation of a free and fair press, not something a president fond of the term “fake news” will ever be synonymous with.

Still, for the many Washingtonians lucky enough to be working from home, six weeks being trapped indoors and fighting with family members about dishes can breed nostalgia for even the most played-out D.C. tradition. The correspondents’ dinner might confirm every worst stereotype of a full-of-itself political class. But anything that involves getting dressed up and actually doing stuff with other people sounds appetizing right about now, especially if it doesn’t involve Zoom.